Good Eats: The Greater Philadelphia Food Economy, and Good Food’s Potential to Drive Growth, Improve Health, and Expand Opportunity

Food fuels more than just our bodies. In Greater Philadelphia, food-based businesses fuel commercial activity and create jobs for thousands of individuals. Businesses and individuals that participate along the food supply chain comprise what we call the “food economy,” whether they are small businesses or multinationals, corner stores or global shippers.

This assessment builds on definitions in the 2011 report, "Eating Here: Greater Philadelphia's Food Systems Plan," from the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC). Drawing from North American Industry Classification Systems (NAICS), the food economy comprises activity within six distinct industry sectors: food production, food processing, food distribution, food retail, food hospitality, and food waste and recovery. Not all businesses fit squarely into one sector. For example, ReAnimator Coffee, a Philadelphia-based coffee company that roasts coffee beans, sells them to businesses and individuals, and operates coffee shops, could be categorized as a processor, retailer, and hospitality business. Though cross-sector business activity like this is common, a sector-based analytical approach allows for comparison and isolation of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and challenges within segments of the food economy.

In Greater Philadelphia today, too few people have access to good jobs, too many communities struggle with high rates of poverty and food insecurity, and economic growth is uneven and inequitable. A good food economy provides living wage jobs, strengthens local supply chains, and supports expanded access to health-promoting food. Finding effective ways to encourage and support food-related commerce, particularly good food businesses, can go a long way in driving growth, promoting health, and expanding opportunity in our region.

Download the Executive Summary or the full report below, or scroll down to interact with the data.

Good Food for Philadelphia

What is Good Food?

Drawn from research done by Get Healthy Philly and the Philadelphia Food Policy Advisory Council (FPAC), this report defines good food as fitting the following four criteria: health-promoting, locally-oriented, fair, and sustainably-produced. Click on the Good Food criteria below to learn more.

Good food is nutritionally dense and nourishing, and does not contribute to chronic disease.

Good food comes from a radius of 250 miles from Philadelphia, encompassing the Greater Philadelphia Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA). This region reaches as far north as New York City, NY, as far south as Washington, D.C., and almost as far west as State College, PA. Locally-oriented food also includes good food produced by Philadelphia area businesses.

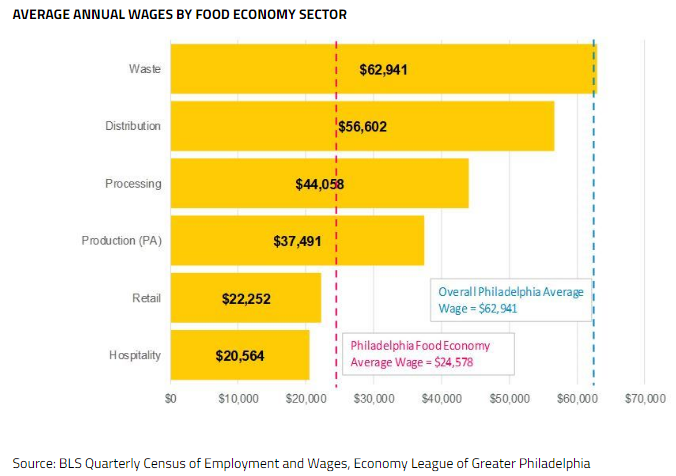

Good food is the product of workplaces that pay family-sustaining wages, provide career pathways, and have healthy workplace environments. For the purposes of this report we define family-sustaining wages using the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Living Wage Calculator’s assessment of regional living wage for two adults and two children. This comes to an hourly wage of $16.35, and an annual wage of $34,008 for the Philadelphia metro area.

Good food is produced using sustainable practices that minimize environmental impact and reduce waste.

The Economic and Social Ripple Effects of Good Food

Philadelphia has the highest rates of unemployment, poverty, and chronic disease incidence among the 10 largest cities in the United States. But support for good food businesses can create new healthy foods, new jobs, and healthier environments, and can harness the extant and growing demand for their goods and services. Click on the ripple effects of good food below to learn more.

Black, brown, and immigrant communities across the region are disproportionately affected by historic discrimination and disinvestment that stunts their opportunities for employment and wealth creation. Non-immigrant people of color are also more likely to experience diet-related disease than white non-immigrants. For a region and city as racially diverse as ours—35.5% of people in Greater Philadelphia are people of color, and 64.2% of Philadelphians are people of color—increasing good food economy job opportunities, particularly in neighborhoods with large proportions of people of color, offers an opportunity to redress these inequities, support better health and economic outcomes, and drive regional growth.

Access to healthy food options is inequitable in the Philadelphia region, and many people reside in areas with limited access to healthy food, and in areas with oversaturation of unhealthy food options. This inequity exacerbates high rates of chronic diseases—one in three adult Philadelphians has hypertension, and one in eight has been diagnosed with diabetes—and reduces the productivity and earning potential of those afflicted. Good food businesses support the health of customers and workers.

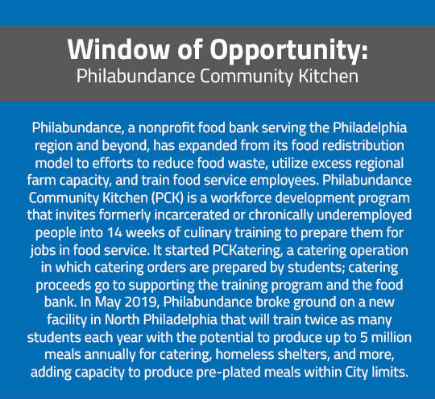

Twenty-six percent of Philadelphians live below the poverty line. Lack of access to opportunity, low educational attainment, weak professional social networks, or previous incarceration can be barriers to finding living-wage work. And while food-based businesses have many entry-level job opportunities—dishwashers, servers —many of those jobs have low pay and high turnover. However, many good food businesses strive to offer living wages and full time work to employees, while all food businesses rely on living wage work that may not immediately be thought of as food-related, like mechanics that repair industrial equipment or transportation-related careers. Food economy careers also provide workforce development opportunities, providing skills and training that can prepares individuals for better paying jobs and advancement opportunities. A food economy with fair workplace practices, targeted training and skills development, and living wages can retain employees, and lift individuals out of poverty.

Black, brown, and immigrant communities across the region are disproportionately affected by historic discrimination and disinvestment that stunts their opportunities for employment and wealth creation. Non-immigrant people of color are also more likely to experience diet-related disease than white non-immigrants. For a region and city as racially diverse as ours—35.5% of people in Greater Philadelphia are people of color, and 64.2% of Philadelphians are people of color—increasing good food economy job opportunities, particularly in neighborhoods with large proportions of people of color, offers an opportunity to redress these inequities, support better health and economic outcomes, and drive regional growth.

Philly Bread and the Good Food Economy

Businesses in Greater Philadelphia are already bringing good food to the mouths, tables, and pantries of area residents and simultaneously supporting the regional economy. Working in food service and urban agriculture, Pete Merzbacher noticed new trends in food processing: he watched the beer and coffee industries localize and specialize, and became convinced that bread would be the next industry to undergo such a transformation. Driven by a passion for food and a penchant for baking, Merzbacher started his business, Philly Bread, in 2013 with his signature local take on the English muffin: the Philly Muffin. Built around creative financing, inclusive hiring practices, regional procurement, regional sales, and large-scale contracts, the way Philly Bread does business is an approach worth replicating.

Click on the business practices below to learn more about how Philly Bread supports the good food economy.

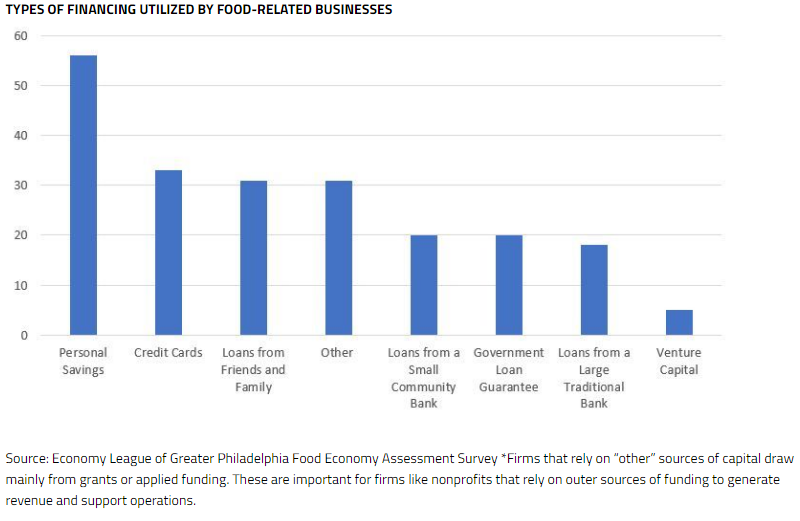

Philly Bread started from personal financing: personal savings, credit cards, loans from friends and family. But from the beginning, Philly Bread capitalized on unique funding sources to finance its growth, including the City of Philadelphia’s KIVA Zip loan and crowdfunding program, and funds from community development financial institutions like PIDC.

Merzbacher and his team believe that even small businesses can support the regional food economy and drive demand by purchasing a segment of their raw goods from other regional firms. The business buys local canola and sunflower oils, as well as a percentage of local whole grain flour, with the aim of growing that percentage in the future. “Farmers aren’t going to grow it unless there’s a demand for it,” says Merzbacher, “and people aren’t going to demand it unless it’s available at a good price. So, if I could work my way up to 1,000 pounds of flour a day, and start with 50 pounds out of a thousand at a premium price, that isn’t going to break my food cost. And then ratchet it up.”

Philly Bread’s entrepreneurial approach has gotten signature products in the door at a wide variety of small local retailers. To date, Philly Bread products have been sold at local retail and hospitality businesses like Square One Coffee, Mariposa Co-Op, and Green Line Café. Selling regionally supports local businesses and employment, keeping money circulating in the regional economy.

While Merzbacher doesn’t exclusively rely on workforce training placement programs to staff the bakery, he has hired candidates through CareerLink and Philabundance programs. Philly Bread’s hiring philosophy supports diversity, welcoming employees that live in the neighborhoods surrounding the bakery as well as formerly incarcerated individuals.

For small food-related businesses, large-scale contracts can provide predictable revenue that can be the key to achieving profitability. In 2017, Philly Bread landed a game-changing contract with national restaurant chain Sweetgreen. Today, Philly Bread’s contract with Sweetgreen accounts for a healthy percentage of its revenue stream, giving the company room to explore growth opportunities.

The Greater Philadelphia Food Economy Today

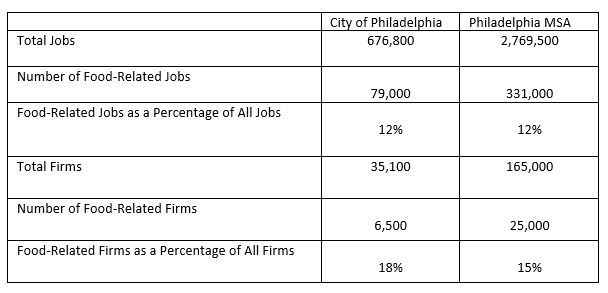

Greater Philadelphia’s food economy supports 331,000 jobs across 25,000 firms in the 11 counties that constitute Philadelphia’s Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA).[1],[2] Philadelphia itself is home to 79,000 food-related jobs across 6,500 firms, accounting for nearly 25% of all food-related jobs and firms in the region—a share that is on par with the city’s share of all regional jobs (24%).[3]

[1] Philadelphia’s MSA includes Bucks County, PA; Burlington County, NJ; Camden County, NJ; Cecil County, MD; Chester County, PA; Delaware County, NJ; Gloucester County, NJ; Montgomery County, PA; New Castle County, DE; Philadelphia County, PA; and Salem County, NJ.

[2] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, 2018, Raw Data (Washington, D.C.: U.S.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, October 15, 2018).

[3] Ibid.

Food Economy Sector Dashboards

Over the past decade, the increase of food-related jobs and firms, and their percentage within the overall regional economy underscores the food economy’s importance to Greater Philadelphia. However, there is tremendous diversity and variation within each of the food economy sectors. Employment, jobs, firms, and projected job growth differ across sectors. Click on the sector dashboards below to learn more about how each sector fares with respect to jobs, job growth, firms, and wages.

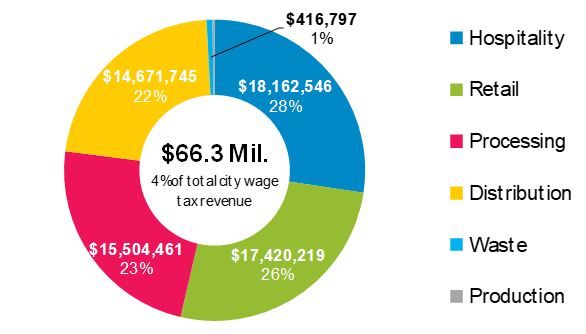

Hospitality

Hospitality includes restaurants, hotels, food service contractors, and caterers. It dominates local food-related employment—supporting 68% of all jobs in the food economy within Philadelphia and 59% of all food-related jobs in the region. The hospitality sector is also one of the primary drivers of food-related job growth at both the city and regional levels, though it pays the lowest average wages of all food economy sectors. It is projected to grow faster than all other food economy sectors over the next five years.

Retail

Retail involves the direct sale of goods to consumers within food and beverage outlets, including online e-commerce platforms. Constituting 21% of city food economy jobs and 25% of regional food economy jobs, retail is one of the largest sources food-related employment in the Philadelphia area. It is also a driver of growth in the city and region, adding over a thousand jobs annually over the past decade. However, regionally it is projected to lose jobs in the next five years, and this sector sees some of the lowest wages across the food economy.

Waste and Recovery

Waste and recovery includes firms engaged in waste collection, treatment, remediation, and food recovery. While it supports the smallest number of food economy jobs, waste and recovery jobs have grown faster than other sectors and projections anticipate continued growth. Waste and recovery also pays the highest average wages in the food economy.[1]

[1] These numbers do not include public sanitation workers or related occupations in the public sector. The City of Philadelphia posts employee salaries publically, however, and a Laborer in the Streets Department, had a starting salary of $32,688 in 2018, while Waste Collection District Supervisors can earn a base pay between $52,000 and $69,000, depending on years of experience.

Distribution

Distribution encompasses transportation, logistics, warehousing, and wholesale of food-related goods. Distribution is the third-largest sector in the food economy with respect to employment, and pays the second-highest average wages. While distribution employment in the city dipped in recent years, growth is projected locally and statewide. The 5,502 distribution firms in the region account for nearly ¼ of all firms in the food economy.

Processing

Processing includes firms that transform raw agricultural products into food products. Employment in this sector is growing regionally, but the city has seen modest annual decline in jobs over the last decade. While it supports fewer jobs than four other food economy sectors, average wages for food processing jobs are higher than many other sectors.

Production

Production includes firms that grow crops, produce livestock products, or support agriculture. Regional employment in this sector is experiencing modest growth, though average wages are low, and it comprises far fewer firms than other sectors of the food economy.

Food Economy Findings

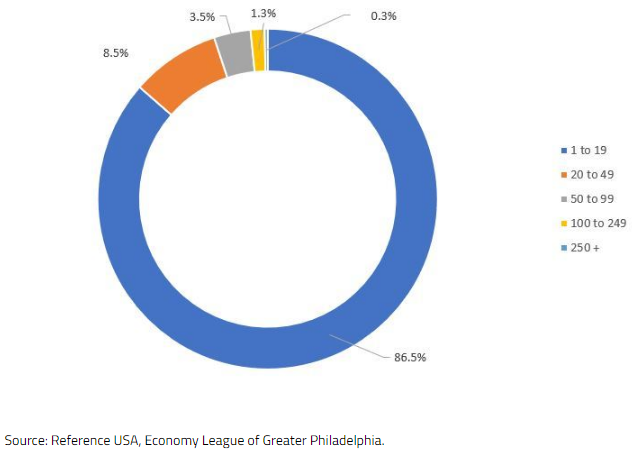

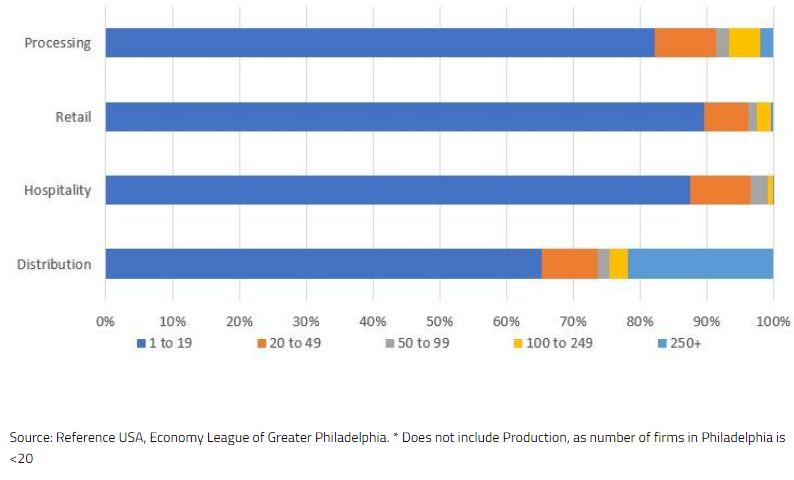

THE MAJORITY OF FOOD-RELATED BUSINESSES ARE SMALL, AND THESE ENTERPRISES SUPPORT MOST OF THE JOBS IN THE FOOD ECONOMY

Ninety-five percent of Philadelphia food businesses have fewer than 50 employees; nearly 9 out of 10 of them have fewer than 20 employees. These small businesses experience challenges not faced by their larger counterparts such as less time for business planning or business administration, and a more limited set of resources. Survey respondents agreed, saying they did not have time to participate in programs to build their business acumen.

FOOD-RELATED BUSINESS SIZE (BY NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES)

PHILADELPHIA FOOD-RELATED BUSINESS FIRM SIZE BY SECTOR (BY NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES)

Hospitality and retail, the two largest employers in the Greater Philadelphia food economy, also have the lowest wages. Low wages may be part of the reason that employees do not stay at a single job long, causing “churn,” or constant hiring due to vacancies, but opportunities still exist for living wage work. Employers are Constantly Hiring : Employers across the food economy, especially those in retail and hospitality, report being in a constant hiring cycle. Unpredictable schedules and low wages cause workers to leave with little or no notice, particularly in retail and hospitality. Meanwhile food-related businesses report difficulty finding qualified workers with basic “soft skills,” citing ‘showing up to work,’ ‘showing up on time,’ ‘work ethic,’ ‘customer service,’ and ‘consistency,’ as top HR challenges. While churn is an operational challenge, it means that there are entry-level opportunities for interested individuals, like returning citizens or those seeking entry-level work for the first time, to enter the workforce. The City of Philadelphia has recently tried to improve working conditions for entry-level retail and hospitality workers by passing legislation for earned sick leave compensation and fair work weeks, which provides for more predictable work shift scheduling. There are Opportunities to Advance Within and Across Food Economy Sectors: With education and certification, workers seeking higher wages within the food economy can find opportunity in waste and recovery, distribution, processing, or even moving to higher-paying, more-stable hospitality jobs. Educational programs such as the Community College of Philadelphia’s culinary arts program provide education in retail and hospitality skills, and can provide job search and placement assistance, and apprenticeship assistance. Entry-level food economy jobs also provide transferrable skills for better paying occupations outside of the food economy. Still, opportunities for advancement to living wage jobs are limited in some sectors. For example, the Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry (DLI) includes supervisor of food preparation and serving workers among its High Priority Occupations (HPOs) in Philadelphia due to the potential for workers to enter into these jobs with minimal educational attainment and advance with experience from an average entry-level salary of $25,240 to family-sustaining wages of $50,500. Yet in 2014, there were only 3,330 food preparation and serving supervisor jobs in Philadelphia, and projections anticipate there to be just 150 openings for this job across the city each year, just a fraction of those working or seeking employment in food businesses.

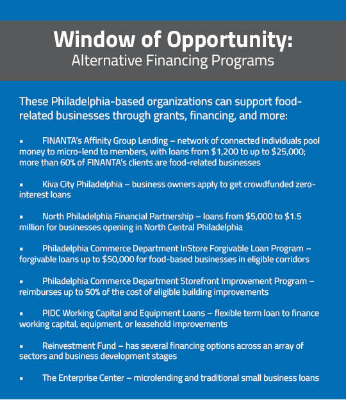

Food-related businesses operate on tight margins and have minimal capacity to absorb losses, and are challenged by fluctuation in food prices and intense competition. These challenges make it hard to turn a profit, and many food-related firms—particularly small ones—are vulnerable to macro- and micro-economic shifts. Due in part to their precarious finances, survey findings suggest that only a small percentage of food-related businesses in the region receive credit from traditional banks, but many are actively seeking additional capital. Business support and financial experts attribute this gap to low financial literacy among businessowners. For minority and immigrant-owned businesses, language and cultural barriers may mean that businessowners are unsure of where to turn for financial planning, are undereducated about what it takes to secure credit, or are treated as higher risk because of lenders’ institutional or implicit bias. Though alternatives to traditional banks and personal financing do exist, including grants and micro-lending, these programs struggle to reach the small business entrepreneurs that could benefit most from their programs. These barriers are the result of and exacerbate the racial wealth gap resulting from previous disinvestment in minority and immigrant communities.

Survey respondents echo industry trends that show that new generations of consumers prioritize socially and environmentally responsible, healthy, local, and customizable foods--in short, good food. These shifts in preferences, driven largely by consumers with disposable income, have helped usher good food to the plates and pantries of residents across the region. It has accelerated the rise of farmers’ markets, handcrafted versions of beverages and foods, meal prep companies, and upmarket grocery stores focusing on local, and oftentimes organic, products. Area institutions are adopting these good food trends, with universities and hospitals in the region aligning their purchasing with consumer preferences and embracing the advantages of regional food systems in curricula and other programming. For example, Drexel University has recently modified their culinary program curriculum to include a focus on how students preparing to enter the food economy can support local producers. Price is an important part of this equation; national trends point to consumer willingness to pay more for high-quality, ethically-produced ingredients. However, it is unclear how much more consumers are willing to pay if factors like transportation costs drive up prices. If prices do rise, large companies that can take advantage of economies of scale will be best positioned to capture the market and put even more pressure on small businesses.

Anchors buy food, contract companies to run their food service operations, lease real estate to food businesses, purchase catering, host farmers markets, and directly or indirectly employ hundreds or thousands of people in food-related occupations. While food may be just part of their business portfolios, quantitative and qualitative data show that patients, students, staff, and visitors increasingly see anchors’ food choices as an expression of their values. Using a good food lens in business decision-making can therefore boost the food economy and anchors’ public profiles. There is also potential for the business community to change to meet anchors’ needs. For example, many anchors, including the City of Philadelphia and the School District of Philadelphia, purchase pre-packaged meals; city officials conservatively estimate that 25 million pre-packaged meals are served to Philadelphia youth each year. Almost all of these meals are produced outside of Philadelphia and trucked into the city daily, and use very few foods from the region. Early childhood education centers, some health care operations, and eldercare facilities also depend on these pre-plated meals that are produced elsewhere. Meeting even a portion of this demand through a variety of mechanisms could mean starting new businesses, creating jobs, and engaging a local supply chain while serving a locally-bound and steady customer base.

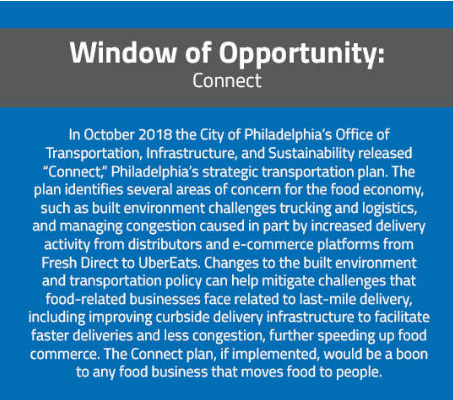

E-commerce and the platform economy have redefined the food economy in just a few years. From grocery delivery via Instacart to making reservations with OpenTable, e-commerce makes the buying and selling of food-related products and services more convenient for consumers through food courier and delivery services. Companies like GrubHub, Caviar, and UberEats are changing the way people purchase food and the way food-related businesses interact with their customers. These changes are spurring typical food businesses to adapt. For example, Sunshine Market, a small full-service grocer in West Philadelphia, began offering delivery services, and now delivers between 20 and 30 grocery orders per day in the first two weeks of every month. But the entrance of retail monoliths like Amazon into food e-commerce has smaller businesses competing against companies that can take advantage of economies of scale and put downward pressure on prices. Meanwhile, more delivery services can lead consumers away from brick-and-mortar hospitality establishments, which may have fewer retail or front-of-house hospitality jobs as a result. The delivery jobs that replace jobs lost to e-commerce are not necessarily equal: most platform workers are independent contractors whose wages are typically lower-paying than their full-time counterparts, and who usually do not receive even basic protections like workers’ compensation. So while e-commerce is a boon to consumers, it may lay vulnerable both entry-level employees and small business growth.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reports that in 2017 the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) generated $1.3 billion in economic activity in Philadelphia County alone, with every $1.00 of SNAP benefits spent resulting in an economic impact of roughly $1.70. Large retailers operating in Philadelphia’s low-income communities estimate that 20%-50% of store revenue is driven by benefit redemption for SNAP and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); for small retailers, SNAP and WIC redemption can be 50% or more of total sales. Nutrition benefits are an important economic driver to area food retailers, but declining SNAP and WIC enrollment and existential threats to the programs themselves may make food retailers and consumers even more vulnerable. According to the National WIC Association, nearly two-thirds of WIC providers from 18 different states nationwide reported declines in immigrant WIC access since 2017, driven in part by immigrants’ fear that participation could put them on the radar of government agencies seeking to deport them. In Greater Philadelphia, that national trend is coupled with low local enrollment: in Strawberry Mansion and Allegheny West, two low-income Philadelphia neighborhoods, approximately 18% of eligible people are not enrolled in food assistance benefit programs, more than the state average. Threats to these programs materialize from time to time, whether in the context of legislating Farm Bill reauthorization, government shutdown, or budget negotiations. When that happens, Philadelphia food retailers of all sizes may see further declines in benefit redemption, leading to fewer sales that could result in layoffs for food retail employees at affected stores.

Starting a food business: More than 1,000 new food establishments open each year in Philadelphia, and all of them have questions about licenses, permitting, and zoning. Entrepreneurs with language barriers or who are new Americans may have even more questions, but may not know how to get them answered. The City offers several services to assist in launching a food business, and continues to pilot new ways of communicating with businessowners. Business support and financial firms also provide support and fill gaps, including for immigrant businessowners who may have language barriers or are unfamiliar with health and permitting regulations required in the United States. Minority Business Resources Interview findings suggest that language barriers, cultural education gaps, and limited access to industry-focused social and business networks are challenges for minority- and immigrant-owned food businesses. While the City of Philadelphia offers materials and translational services in multiple languages, some non-English speaking business owners do not know that resources in their language are available. Business support and financial firms also report that many of their immigrant clients are unfamiliar with health and permitting regulations required in the United States. Taxes and Fiscal Policy Challenges In Philadelphia, sales tax, business income and receipts tax (BIRT), wage taxes, the Philadelphia Beverage Tax, liquor tax, dumpster fees, and cigarette licenses comprise the tax responsibility for food-based businesses. In recent years, while the beverage tax has garnered significant media attention, the City made policy adjustments and introduced resources to ease the impact of multiple taxes. One example of this is the City’s Special Committee on Regulatory Reform’s recommendation for changing second-year payment terms for the BIRT, which many food-related businesses said substantially increases their tax payment burden in their second year of operation. And yet, while businesses across all sectors indicate that taxes are a primary concern, they do not factor into choosing a location to do business: when asked about locating their businesses, ‘local taxes’ ranked as the least important decision-making factor by survey respondents.

Opportunities for Good Food to Grow Greater Philadelphia's Food Economy

Food retail and hospitality businesses that prioritize regionally-produced ingredients struggle against the Mid-Atlantic growing season. From small catering companies to national food service management companies, interviewees and survey respondents say our region’s limited growing season makes it hard to commit to regional sourcing. A centralized facility—one that could preserve the regional harvest and produce meals from that bounty—could solve multiple problems with one good food solution. It could process regionally-grown fruits and vegetables into frozen and shelf-stable products to be used year-round by all types of food businesses; it could produce pre-plated meals that make use of those same good food ingredients; it could provide local jobs in processing, food production, and distribution; and it could commit Philadelphia anchor institutions to good food procurement. No small investment, such an operation would require partnership and investment across public, private, and non-profit sectors, but could manifest demonstrable benefits to producers, retailers, hospitality firms, and eaters.

Survey respondents from retail and hospitality firms, particularly those that aim to support regional producers and processors, struggle to meet delivery minimums from distributors. “We order too much [to buy from] small farms, and not enough for big distributors,” says one respondent, who runs a small locally-focused retail shop. Last-mile distribution—or transporting goods from their final distribution site to the customer—is expensive: labor, vehicle purchase and maintenance, fuel, and parking tickets must be calculated into the cost of each delivery. It is more efficient to deliver a truckload of food to one customer than to 25 customers in a dense urban area, so distributors pass along the cost of this inefficiency to the customer by having minimum order amounts or “drop sizes.” The rise of e-commerce now sees more trucks making more stops, adding to congestion and increasing inefficiency. A business that could figure out how to circumvent these inefficiencies would be a huge boon to Philadelphia food businesses that struggle to meet distributor minimums. In Portland, OR, B-Line Sustainable Urban Delivery is tackling last-mile distribution using tricycles with refrigerator boxes and providing a suite of delivery and logistics services for good food businesses. Similar ingenuity may find strong demand from Philadelphia food businesses.

Anchor institutions hold significant high-traffic real estate in Philadelphia, including spaces for food-related retail and hospitality businesses. When anchors adopt policies that include a preference for local operators when searching for food-related tenants, they stimulate and support regional small business activity, and expand access to good food in the region. Franklin’s Table, a food hall at the University of Pennsylvania that opened in 2018, incorporated preferences for local and regional firms in their lease agreements, and several restaurants from Philadelphia and its environs have set up shop. Though Franklin’s Table hits the mark on local business support, its price points miss on accessibility: West Philadelphia is economically and socially diverse, but Franklin’s Table prices are a better fit for wealthy students than working class residents.

Philadelphia is home to a few companies that collect organic food waste for composting, but the potential for organics collection is far from realized. Tim Bennett, owner of Bennett Compost, grew his business from his second floor apartment in 2009 to a seven-person operation collecting food scraps from over 2,000 residential customers in Philadelphia. Bennett says he started seeing record-numbers of sign-ups for his company’s services month over month in 2018, “but that’s still less than 1% of households in the City.” Hospitality firms are eager to find companies to manage their food waste. Survey respondents are also seeking compostable food service materials, and will need a place to send them. According to the Center for EcoTechnology, which partnered with the City of Philadelphia to evaluate opportunities and barriers to diverting food waste, one of the biggest barriers for businesses seeking to keep food waste out of landfills is the lack of compost facilities within Philadelphia. Bennett sees an opening for local small business in organics collection and management, even as his business continues to grow: “Probably at some point…a decision has to be made as to whether the solution for [organics collection in Greater Philadelphia] is to have one or two giant facilities in the region to handle all of the material, or whether you can have a bunch, a little ten to twenty -- not even small [companies], but midsize ones.” Though state regulations make commercial composting difficult in Philadelphia, small- to mid-sized businesses may be a right-fit for our population-dense region, providing good jobs and improving the environmental impact of the food economy.

Good Food Partnership Opportunities

City departments and agencies have been taking strides to develop supportive policies and programs that improve the business environment for all food businesses. Some initiatives, like the guides to opening food businesses [LINK], put out jointly by the departments of Public Health, Licenses & Inspections, and Commerce, aim to clarify City processes. A new initiative by the same group is going further, surveying businesses as they apply for licenses on their needs and ways departments can better communicate with them. A focus on good food businesses was spurred by the Philadelphia Food Policy Advisory Council, which recommended that the City purchase more food, including catering, from good food businesses. It developed and released a Good Food Caterer Guide, which directs City employees and others to local restaurants and caterers that provide healthy and sustainable options, and employ fair labor practices. City procurement processes followed suit, engaging good food vendors to find ways to improve its contracting processes, including streamlining bid templates and adding good food reporting requirements to assess the City’s progress in purchasing more good food, and in turn supporting more good food businesses. Other supports being piloted include recent legislation that permits food retailers to have racks of fresh fruits and vegetables against their storefronts on the sidewalks, increasing the visibility and appeal of healthy foods, as well as two small grant programs for good food businesses. The first, the Healthy Food Business Program, is a partnership between the Commerce Department and the Department of Public Health to provide technical assistance and access to City grants and forgivable loans for qualified businesses that sell healthy food or otherwise promote health. The second, the Food Justice Grant, is a mini-grant program aimed at neighborhood businesses and organizations looking to increase the availability and appeal of healthy foods, particularly in areas with low access to healthy food. Both programs, in their first year in 2019, if expanded could assist even more area businesses.

Personal savings, credit cards, and loans from friends and family were the three common financing mechanisms food businesses, according to survey responses. Aspiring food business owners often see no other choice but to take on the enormous personal risk of those options, as many food-based entrepreneurs cannot get sufficient financing from a traditional bank. Several organizations and programs in Greater Philadelphia provide alternatives to personal financing. Philadelphia Department of Commerce can provide Philadelphia businesses or those looking to start businesses in the City with guidance about which programs may be right for them. In many instances, less-than-perfect credit does not necessarily mean a loan application will be denied. In 2019, the Philadelphia Commerce Department and Get Healthy Philly explored explicitly targeting good food businesses for this type of education and funding through their Healthy Food Business Program. Three businesses were selected to receive food business-related technical assistance and access to the Commerce Department’s suite of business improvement programs. More programming and funding tailored to the needs of good food businesses could further boost their financing acumen and connectivity to other resources.

Good Food Policy Opportunities

The City of Philadelphia spends over $25 million annually on food and food services for programs run by its departments and agencies like Prisons, Parks & Recreation, and the Office of Homeless Services. While the City purchases less food each year than the School District of Philadelphia and many area anchor institutions, the City could lead by example in purchasing nutritious food that is sustainably raised on regional farms, purchased from local businesses, and support fair labor practices across the supply chain. The FPAC Good Food Procurement Subcommittee formed out of a group looking at local food purchasing in 2015, and advocated to Philadelphia City Council that purchase of good food be part of a citywide sustainable procurement plan. Greenworks, the plan published by the City’s Office of Sustainability, similarly prioritizes sustainably- and locally-procured food. And in 2017, with the support of FPAC and the Office of Sustainability, the Department of Public Health created a cross-departmental position to implement good food purchasing practices. Since 2017, the City has worked with the Center for Good Food Purchasing to evaluate food purchases for four departments, and found successes and opportunities for more good food procurement including increasing supply chain transparency to make it easier to know where food comes from; reducing the amount of processed meat served in favor of plant-based proteins and smaller amounts of sustainably-produced meat; and purchasing more fresh and frozen vegetables from the region. Philadelphia can support the health of the local economy, the health of our regional environment, and the health of the people it serves—children and youth, people experiencing homelessness or incarceration, the elderly—by committing to purchasing good food.

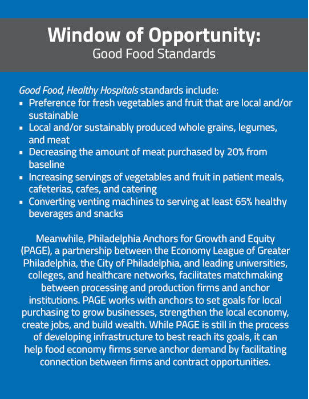

Anchors purchase and serve an enormous volume of food; for example, the dormitory food operations at the University of Pennsylvania alone utilize 1.2 million pounds of food per week. For small production and processing firms that can win even a portion of an anchor’s business, that can translate to an important and constant stream of revenue. When anchors invest in small businesses, they lay a foundation for business stability and growth. Many anchor institutions in Philadelphia, particularly hospital systems, have adopted voluntary nutrition guidelines for the food they serve. Through the Good Food, Healthy Hospitals initiative, hospitals commit to improving the nutritional quality and local impact of patient meals, food retail, catering, and vending. To date, 18 hospitals have made the pledge, representing $X million in food purchases.

Food-based retail and hospitality, the two largest food-related employment sectors in Greater Philadelphia, also have the lowest wages; average annual wages in those sectors come out to $10-11 per hour. These sectors also have high turnover and few opportunities for benefits or paid leave. While earned sick leave and fair scheduling legislation may help, the primary way to lift low-wage workers out of poverty is to raise the minimum wage. Raising the minimum wage for food economy workers in retail and hospitality will improve their livelihoods and get more money circulating in the regional economy. This will be of particular importance to groups for whom low-wage jobs in retail and hospitality are an entry point into the workforce, such as returning citizens, or lower-income groups across Philadelphia. For employers, employees who are paid better are less likely to leave, reducing the time and expense of hiring and training new employees. Though Philadelphia is preempted by the state from raising its minimum wage, there is a growing effort to pressure state lawmakers to pass legislation statewide. Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf signed an executive order to raise the minimum wage for State employees to $12. In December 2018, Philadelphia mayor, Jim Kenney signed the 21st Century Minimum Wage Law, which will gradually raise the minimum wage for city-paid workers from $12.20 to $15 an hour. Policies that support these efforts by preferentially supporting businesses that pay higher starting wages would have impacts far beyond the food economy.

Good Food Product Opportunities

Consumer demand is trending toward health-promoting and environment-conscious products and businesses, and foods from many cultures. Survey and interview respondents noted that formerly-fringe food demands, from vegan baked goods to rare imported fruits and vegetables, are now mainstream. Sunny Phanthavong, owner of Vientiane Bistro in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, sees an overlap between health and ethnic cuisine. “Philly's just a good, dynamic food city [and] it keeps getting better. People are wanting to try new foods, [and are] more health conscious." Vientiane serves vegan and vegetarian items, and has seen a boon from people choosing plant-based diets for health, religious, environmental, or ethical reasons. Trends toward plant-based, vegetarian, and vegan preferences also show continued popularity. Philadelphia hosted its first Vegan Restaurant Week in 2018, with 19 restaurants participating; in 2019, more than 40 restaurants have signed on to serve vegan fare. Though vegan restaurants in Philadelphia are not new—there have been small outposts of vegan-friendly fare in South Philly, West Philly, and Germantown for years—the new wave of options across the city suggests that plant-based dining is growing in popularity. Also expanding is the demand for fruits and vegetables associated with the cuisine of Greater Philadelphia’s immigrant communities. The demand has grown and changed, says Emily Kohlhas, Director of Marketing for John Vena, Inc. a 100 year old fresh produce wholesaler and a cornerstone of the massive Philadelphia Wholesale Produce Market. Recently, demand has grown for tropical fruits, peppers, and other produce common in Central American cuisines as Greater Philadelphia becomes home to more people from the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and elsewhere in the Americas. While restaurants serving this food to a broader audience is part of the trend, Kohlhas says “sustained demand from people who eat this type of food every day” is what keeps things like chayote, nopal, and calabacita in stock at the massive Market.

Consumer trends and nutrition requirements from federal food programs have businesses looking for healthier alternatives to some popular foods. Matt Luchansky, Senior Vice President of Novick Brothers, a food distributor in South Philadelphia, says it would be much easier for his business to serve early childcare centers if more of the foods that meet centers’ food program requirements were made locally. “I know there's pasta places all throughout the City. What can they produce for me? Why do I have to go to the Bronx [where a manufacturer is] producing whole grain pasta? You're right here. I don't want to have to pick it up in Queens.” Drexel Food Lab, a recipe and product development laboratory at Drexel University, works with food manufacturers to develop and test product formulations. Nutrition and sustainability are often in focus during these developments, and Drexel Food Lab has worked with food companies to make great tasting food that is better for people and the planet. In partnership with Get Healthy Philly to reduce sodium in popular foods, it recently assisted F&S Produce in Vineland, NJ in developing fresh vegetable-based deli salads to replace typical mayonnaise-based options; worked with Comcast Spectacor to develop a beef burger blended with mushrooms; and worked with New Jersey-based Amoroso’s Baking Company to develop a lower-sodium, whole grain-rich hoagie roll for schools and hospitals. “Most of the manufacturers we speak with are perfectly happy to supply healthier food if indeed the market is there for them,” says Jon Deutsch, Founder and Director of the Drexel Food Lab and Professor of Food Studies at Drexel University. “Reducing calories, fat, salt and sugar, and increasing nutrient density while still making something delicious and craveable can be a challenge, and even changing one ingredient can be expensive for a manufacturer. Manufacturers need to know that their efforts to reformulate existing products to make them healthier or to introduce new healthy products will translate to sales. Drexel Food Lab’s expertise involves working with manufacturers to develop and reformulate good food products that contribute to more sustainable, healthier, or more accessible food while tasting great.”

Distributors, retailers, and hospitality firms continue to demand more local ingredients, including fruits, vegetables, dairy, grains, and meat and poultry. Demand comes from consumers, and from internal policies to support regional agriculture. Bon Appétit Management Company, which manages food service at the University of Pennsylvania, requires its chefs to purchase 20% of their food from within 150 miles of Philadelphia and to prioritize purchasing from small farms and firms. The company is even hiring its own “forager,” a specialized position at UPenn that will help locate and set up agreements with local farms and firms. Without the resources to hire a forager, however, food businesses rely on a few key distributors and word of mouth to find purveyors. Some, like The Common Market, specialize in local sourcing, while others that have sourced from the region for decades are finally labeling their local product. “We’ve always been buying local, but now we put more branding around it,” says Jason Hollinger of Four Seasons Produce. Several distributors have begun identifying local product by farm name to make it easier for restaurants and retailers to purchase locally. That does not mean that demand has levelled off. Hospitality firms note that the growing season around Philadelphia limits their options in winter and early spring, and that they would like to purchase more types of foods locally, including manufactured foods made from local ingredients. Bakeries, breweries, ice cream companies, and pasta-makers are on the constant hunt for grain growers, mills, dairies, and egg-producers to supply raw ingredients for their products.

Methodology and Data Limitations

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, using local and national quantitative data, surveys, and interviews to illustrate the nuances of food-related business operations and relationships. The quantitative analysis examines wage and labor data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, tax revenue data from the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Revenue, wage data from PayScale, and firm-level data from ReferenceUSA. These datasets include several limitations. For one, the availability of industry data varies by geography. BLS employment data is not equally available for all industries at all geographies (e.g. national, state, metro, county). To address this variability, this study collected county-level BLS employment data and then aggregated it across the 11 counties that make up the Philadelphia MSA. Additionally, industry-level data for the waste and distribution sectors encompass a large percentage of firms that fall outside of the food economy. For example, distribution includes general warehousing, and rail and freight transportation. As such, this analysis factors in that industry-level data for these sectors is 15% of the total industry.

The qualitative analysis draws from intelligence gathered through 20 interviews with key firms across food economy sectors, focus groups with anchor institutions, and an in-depth survey of 76 food-related businesses. While the quantity of survey responses collected is sufficient to draw some conclusions about food-related business activity in the region, it is not an exhaustive accounting of all opportunities and challenges facing food-related businesses in Greater Philadelphia. As such, this report articulates priority strategies for supporting the region’s food economy and openly acknowledges areas where further study is necessary to better understand specific dynamics and opportunities.

The food economy includes an unknown but significant amount of informal economic activity—that is, businesses that are cash- or barter-based or otherwise not traceable by traditional tools for gathering economic data. For example, unlicensed produce brokers, or “jobbers,” distribute food from farms or wholesale markets to small food businesses in the city, like produce markets or corner stores; however, a lack of reliable data and formal research limits understanding of the overall economic impacts of these transactions. Similarly, it is difficult to measure the economic contributions of undocumented immigrants who work “off the books” on farms, and in restaurants and hotels. Though the food economy relies on their labor and skills, the informal nature of their employment, as well as current federal attitudes toward immigration status, make it difficult to quantify the scale and impact undocumented immigrants’ participation in the food economy.

Other forms of informal employment and earnings are similarly hard to measure. “Off the books” wages and unreported cash gratuities in the hospitality sector make it difficult to accurately measure economic impact. Urban agriculture is also part of an informal food economy, whether demand substitution, where gardeners and farmers supplement or substitute their own or their neighbors’ food needs by giving away produce, or via employment in small-scale urban agriculture not captured in formal employment data. Also, as many Philadelphia urban farms are part of nonprofits, farm labor may be categorized in the quantitative datasets as nonprofit labor. While this analysis briefly addresses some of these gaps, these topics would benefit from further study.

Acknowledgments

The City of Philadelphia Department of Public Health Division of Chronic Disease and Injury Prevention and the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia would like to thank members of the Food Economy Assessment steering committee and project team for their input and guidance throughout this study. Members’ broad expertise, ability to facilitate important information-gathering connections, and perspective across a wide set of issues were critical to developing the analysis and strategic framework for this report. Thank you to the dozens of individuals who made time to fill out the survey and the key stakeholders and firms that took the time for interviews. Thanks to the Reading Terminal Market, the Mid-Atlantic Regional Cooperative, Fernando Suarez Business Advisors, and the Greater Hispanic Chamber of Commerce and Oscar Calle-Palomeque for assisting with survey collection. The Economy League would also like to thank Sydney Goldstein of Urban Spatial and Danielle Dong of JacobsWyper Architects for assistance with spatial analysis; Spencer DeRoos and Carmen Esposito for their contributions to literature review and background research; the team at Untuck for their graphic design expertise; and Thaddeus Woody for his insight on the status of relevant federal legislation.

This report is funded through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Sodium Reduction in Communities Program Grant.

Steering Committee

Jennifer Crowther – Vice President, Product and Resource Development, PIDC

Jonathan Deutsch – Professor, Center for Food and Hospitality Management and Department of Nutrition Science, Drexel University

Megan Bucknum Ferrigno – Professor, School of Earth and Environment, Rowan University

Benjamin Fileccia – President, Philadelphia Restaurant and Hotel Alliance

Molly Hartman – Program Director, Healthy Food Financing Initiative, Reinvestment Fund

Alison Hastings - Manager, Office of Communications and Engagement, Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission

Beth McGinsky – Director of Data and Evaluations, The Enterprise Center

Donna Leuchten Nuccio – Director, Healthy Food Access, Lending & Investments, Reinvestment Fund

Ashley Richards – City Planner, Planning Division, Philadelphia City Planning Commission

Anna Shipp – Executive Director, Sustainable Business Network of Greater Philadelphia

Jonathan Snyder – Director, Business Financial Resources, Office of Neighborhood Economic Development, Department of Commerce

Project Team

Jennifer Aquilante – Food Policy Coordinator, Get Healthy Philly, Philadelphia Department of Public Health

Hannah Chatterjee – Food Policy Advisory Council Manager, Office of Sustainability, City of Philadelphia

Ben Logue – Get Healthy Philly, Philadelphia Department of Public Health

Molly Riordan – Good Food Purchasing Coordinator, Get Healthy Philly, Philadelphia Department of Public Health

Mohona Siddique – Economy League of Greater Philadelphia

Nick Frontino – Economy League of Greater Philadelphia

John Taylor – Economy League of Greater Philadelphia

Amanda Wagner –Nutrition & Physical Activity Program Manager, Get Healthy Philly, Philadelphia Department of Public Health

Executive Summary Graphic Design Team

Amy Saal - Untuck

John Saal - Untuck

Julie Rado - Untuck