Detroit: Past and Future of a Shrinking City

We continue our Leading Indicator series focused on Detroit as we prepare to convene 150 Philadelphia civic and business leaders for the Greater Philadelphia Leadership Exchange (GPLEX) in Detroit this October. In this edition, we examine the Motor City’s decline in industrial activity and population in the second half of the twentieth century as well as some of the approaches it is adopting to revitalize its urban landscape.

What You Need to Know

- The heavily automobile-centric industrial landscape of Detroit, established in the first half of the twentieth century, led to rapid declines in population and economic output after automotive decentralization.

- Detroit experienced a 61.4 percent decrease in population from 1950 to 2010, lowering its ranking from the fourth most populous city in the U.S. to the twenty-seventh.

- By 2012, Detroit had 40 square miles of vacant land out of a total of 139 square miles. This means that a third of the total land area of Detroit was vacant in 2012.

- Between 2005 and 2015, 1-in-3 Detroit properties have been foreclosed.

- Current land use in Detroit shows that higher neighborhood vacancy rates proliferate just outside Detroit’s downtown in the neighborhoods just to the northwest along Grand River Ave and in the northeast at the end of Gratiot Ave.

- Neighborhoods that have a lower population density are predominantly occupied by Black residents.

- Detroit has a high demolition rate which is common among shrinking cities, but new construction activity can be seen around Detroit’s downtown area and some surrounding neighborhoods, like Corktown and Midtown. There are also some outlying patches of new construction around the North End neighborhood, near Henry Ford hospital, and in the northwest section of the city.

- In recent years, city planners have started introducing initiatives to tackle land use issues in Detroit. Greenways Coalition is one of the biggest initiatives that hopes to improve the safety and mobility of commuters in the city of Detroit by connecting different neighborhoods via bike lanes and running trails.

- Ford and Google are collaborating to develop the Innovation District in Michigan Central to develop new mobility technologies and create new workforce development opportunities through technical certifications.

- Small business coalitions, like Live6 Alliance, are using place-based urban planning to revitalize economic growth in depilated commercial corridors.

Detroit’s History of Decline

Detroit has been one of the most salient examples of a shrinking city over the last 60 years. A phenomenon experienced worldwide and occurring most frequently in industrialized countries, shrinking cities are urban areas that have experienced population loss, economic downturn, employment decline, and social problems as symptoms of a structural crisis [1]. By 2010, Detroit had seen a 61.4 percent decrease in its population since its peak in 1950 [2]. In fact, in terms of population, Detroit was the fourth biggest city in the U.S. in 1950, after New York City, Chicago, and Philadelphia. However, according to the 2021 Current Population Survey, Detroit ranks as the twenty-seventh most populous city in the country. As we have outlined in our previous Leading Indicators [2,3], Detroit's population exodus resulted from both the incentive of suburban living among middle-class white residents as well as the decentralization of the automotive industry. The combination of these factors started a chain reaction of businesses and middle-class populations exiting the city for the suburbs. What was left behind were impoverished populations—who were often structurally barred from moving to new economic opportunities—and a hollowed-out tax base. As a result, the city lacked the funds and resources to prevent a further slippage into poverty among many residents and to provide the services that would keep the middle class from moving away; Detroit's poverty rate sharply increased from 14.9 percent in 1970 to 33.2 percent as of 2021 [4].

Abandoned Houses in Detroit

This story of economic decline, caused by rapid industrial decentralization, has been repeated in other cities around the U.S. as well, including Pittsburgh, St. Louis and Cleveland [5]. However, none have experienced the depth and breadth of abandonment of residential and commercial buildings seen in Detroit over the last six decades. According to a 2012 report by Detroit Future City, there were almost 40 square miles of vacant land out of Detroit's total of 139 square miles. This means that abandoned land amounted to a third of the total land area of Detroit in 2012. Detroit is filled with visual landmarks of a shrinking city, where a scattering of abandoned industrial sites and skyscrapers are constant reminders of the impact of decentralized industries on central cities. Some of the most famous examples include the Packard Automobile Manufacturing Plant, built in 1907 as the most modern and massive manufacturing facility of its kind that has been empty and deteriorating since 1956. The list also includes the Fisher Body Plant 21 built in 1919 and vacated in the 1990s and the Michigan Central Rail depot built in 1913 and abandoned in 1988 [6]. Foreclosures further added to the poor land use issue in Detroit. Foreclosures occur when homeowners and financial institutions cannot pay property taxes or mortgage payments owed on their buildings and they are repossessed by the state, county or local governments. Between 2005 and 2015, 1-in-3 Detroit properties have been foreclosed totaling 139,699 homes [7].

Abandoned Factory in Detroit

Some of the roots of Detroit’s urban decline lie in the way the city was planned in the first half of the twentieth century. The unbroken arc of automotive factories that ran along the Detroit Terminal Railroad (DTR) in 1910s essentially blocked the downtown from spreading outwards into the neighborhoods [8]. This residential bottleneck coincided with increased demand for housing as the population of Detroit increased in the wake of WWI. In order to meet this demand, the city’s real estate industry developed single-family houses, almost exclusively, in the neighborhoods beyond the DTR. As decentralization of the automotive industries began in the 1950s, these factories lining the DTR were abandoned, leaving large tracts of urban ruins on the outer rim of the downtown that complicated future development. In addition, the single-family housing districts outside the DTR were so vast that they could not be repurposed for alternative development by the city government. Their cape-cod design and poor construction quality further lowered demand for housing in the city in the ensuing decades.

Abandoned Factories in Detroit

Coupled with the constraints of the built industrial environment was the lack of a comprehensive public transit network in Detroit. Unlike many of its peers, Detroit did not invest in light rail or subway systems in the early twentieth century. It utilized a network of streetcars that were eventually replaced by a bus system - at the behest of General Motors [9]. By the time the federal government began subsidizing the creation of highway systems, the lack of public transit and the ease of the automobile further incentivized populations to live farther from the downtown in the surrounding suburbs. The combination of these planning factors along with the structural shift in the automotive industry created a perfect storm and contributed to the dramatic shrinkage of Detroit well into the twenty-first century.

Current State of Land Use in Detroit

Land vacancy rates are a key indicator of a shrinking city. As populations, economic opportunities, and social services contract, the number of vacant properties tends to increase. A combination of factors—like the cost of maintenance, tax burden, persistent unemployment, and low market demand—can all make continued occupancy infeasible [10]. These vacant properties either sit and decay or are demolished leaving the city’s landscape blighted with ruined structures or open unused land.

High rates of land vacancies have persisted in Detroit into the twenty-first century. Measuring building vacancy rates can be difficult, given that city officials or researchers need to physically examine each individual land parcel within a city (a Herculean task). In 2014, Data Driven Detroit, a local employee-owned cooperative focused on providing open data resources and data literacy to inform better decision-making in Detroit, triangulated a variety of administrative and proprietary data sources to estimate the likelihood of vacant land parcels in the city. Figure 2 illustrates estimates of Detroit’s vacant properties using Data Driven Detroit’s “highly likely” estimate.

FIGURE 1

SOURCE: Data Driven Detroit

Figure 2 shows how higher neighborhood vacancy rates proliferate just outside Detroit’s downtown – in the neighborhoods just northwest of the downtown area along Grand River Ave and in the northeast at the end of Gratiot Ave. As figure 3 shows, these areas have low population densities and are predominantly occupied by Black residents.

FIGURE 2

SOURCE: Data Driven Detroit and five-year estimates of the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2020 American Community Survey.

Like vacant properties, the share of demolition and new construction activity can illustrate a shrinking city’s development patterns. Shrinking cities often see minimal to no new construction activity while seeing a large amount of demolition activity. These demolitions are usually carried out on long abandoned properties by, or at the behest of, the city itself. They are a means for curbing blight and illegal activity [11]. Figure 4 details recently issued new construction and demolition building permits within Detroit from January 1, 2019 to July 19, 2022.

FIGURE 3

SOURCE: Detroit’s Open Data Portal

Figure 4 shows that new construction activity has consistently been centered around Detroit’s downtown area and some surrounding neighborhoods, like Corktown and Midtown. There are also some outlying patches of new construction around the North End neighborhood, near Henry Ford hospital, and in the northwest section of the city. Demolitions remain a common feature of the surrounding neighborhoods.

Looking to the Future

The unique problems in the wake of severe shrinkage in Detroit call for a new approach to solving complex issues like vacant land use. The traditional growth model does not work for cities like Detroit that have structural problems of supply and demand when it comes to retaining human capital and sustained business activity. Fortunately, this also gives city planners and entrepreneurs in Detroit an unprecedented opportunity to write a new playbook on innovative solutions that can revitalize Detroit’s substantial vacant land tracts [12]. In recent years, a combination of big companies as well as coalitions of small businesses have started addressing the long-standing problem of poor land use in Detroit.

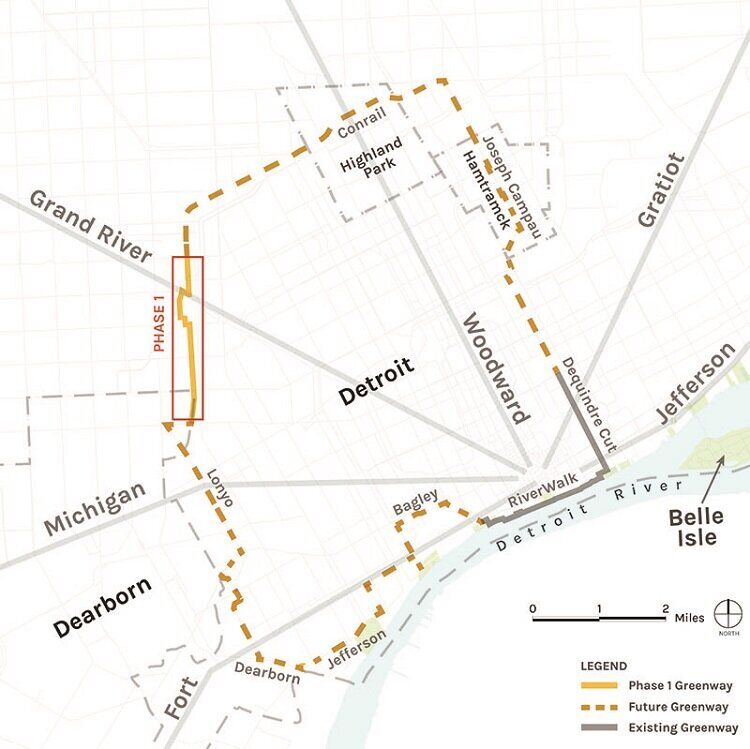

One of the most significant initiatives to improve the urban landscape in Detroit is driven by the Greenways Coalition. Greenways Coalition is an effort to improve the safety and mobility of commuters in Detroit by connecting different neighborhoods via bike lanes and running trails. By leading the charge on extensive greenways that can connect every corner of the city, the Greenways Coalition hopes to bring safe mobility back to the City of Detroit. The Joe Louis Greenway, for example, will be one of the biggest Greenway projects in the U.S. at 27.5 miles and will connect the Detroit Riverfront to Highland Park, Dearborn, and Hamtramck [13].

Detroit's Greenway Project

In addition to physical changes to the urban landscape, large US-based companies also started investing in the economic landscape and workforce development of Detroit. One of these investments includes development of the Innovation District at Michigan Central through a collaboration of Ford and Google. Once a dilapidated railroad station that was abandoned in 1988 after train service stopped, Michigan Central is becoming a mobility-focused innovation district where Fortune 500 companies and government agencies are collaborating to design the future of U.S. mobility. Ford is working on developing electric powered vehicles in the innovation district at Michigan Central, while Google is providing cloud technology to develop software for the next generation of vehicles [14]. In addition, Google is also offering workforce development and skills training to local high school students through Code Next Lab at Michigan Central [15]. Collaboration between Fortune 500 companies like Ford and Google has the potential to not only bolster Detroit’s existing manufacturing sector but also revive its historical status as a hub for automotive innovation. To support this collaboration, the State of Michigan has also allocated $126 million in funds to reconstruct Michigan Avenue and develop new housing districts around Michigan Central. This innovative public-private partnership could mitigate some of the issue of land holes in Detroit.

For a truly inclusive recovery, investments by large corporations are not enough; small businesses must also grow and benefit from new economic opportunities. Non-profit organizations, like Live6 Alliance, are providing crucial networks, knowledge expertise, and even implementation support to small businesses to re-populate deserted commercial corridors. These partnerships are vital for a more equitable distribution of socioeconomic gains. The recent influx of investment in the downtown neighborhoods, especially through Bedrock Companies, has created a socioeconomic divide between the downtown and surrounding neighborhoods of Detroit. Coalitions of community leaders and city stakeholders, like Live6 Alliance, can address this inequity by providing resources to small businesses that are otherwise inaccessible.

Conclusion

Over the past 60 years Detroit has gone through a traumatic experience of unprecedented urban shrinkage. Abandoned buildings and high household vacancies turned several Detroit neighborhoods into ghost towns. However, place-based approaches to revitalization in recent years by coalitions like Live6 Alliance coupled with Greenways infrastructure and investments by Fortune 500 companies promise to turn a new leaf in Detroit’s socioeconomic history. With appropriate civic oversight there are reasons for cautious optimism that the benefits of the recent flurry of investment might be distributed equitably.

Works Cited:

[1] Cristina Martinez-Fernandez, Ivonne Audirac, Sylvie Fol and Emmanuele Cunningham-Sabot. 2012. “Shrinking Cities: Urban Challenges of Globalization.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research.

[2] Mike Shields and Haseeb Bajwa. 2022. “A Philadelphia-Detroit Comparison: The Economies.” Economy League of Greater Philadelphia. Retrieved from: (https://economyleague.org/providing-insight/leadingindicators/2022/07/13/phillydetroit2)

[3] Mike Shields. 2022. “A Philadelphia-Detroit Comparison: The Populations.” Economy League of Greater Philadelphia. Retrieved from: (https://economyleague.org/providing-insight/leadingindicators/2022/06/29/phillydetroit1)

[4] Quick Facts. 2022. U.S. Census Bureau and American Community Survey. Retrieved from: (https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/detroitcitymichigan/PST120221)

[5] Scott Beyer. 2018. “Why Has Detroit Continued to Decline?” Forbes. Retrieved from: (https://www.forbes.com/sites/scottbeyer/2018/07/31/why-has-detroit-continued-to-decline/?sh=385f92ed3fbe)

[6] June Manning Thomas and Henco Bekkering. 2015. “Mapping Detroit: Land, Community and Shaping a City.” Wayne State University Press.

[7] Kurth J., MacDonald, C. 2015. “Volume of abandoned homes absolutely terrifying.” The Detroit News. Retrieved from: (http://www/detroitnews.com/story/news/special-reports/2015/05/14/detroit-abandoned-homes-volume-terrifying/27237787/)

[8] Aaron Renn. 2012. “Nine Reasons Why Detroit Failed.” Aaron Renn. Retrieved from: (https://www.aaronrenn.com/2012/02/21/the-reasons-behind-detroits-decline-by-pete-saunders/)

[9] Aaron Renn. 2012. “Nine Reasons Why Detroit Failed.” Aaron Renn. Retrieved from: (https://www.aaronrenn.com/2012/02/21/the-reasons-behind-detroits-decline-by-pete-saunders/)

[10] Esmat Ishag-Osman. 2022. “Examining Detroit’s Vacancy Rate Drop.” Citizens Research Council of Michigan. Retrieved from: (https://crcmich.org/examining-detroits-vacancy-rate-drop)

[11] Esmat Ishag-Osman. 2022. “Examining Detroit’s Vacancy Rate Drop.” Citizens Research Council of Michigan. Retrieved from: (https://crcmich.org/examining-detroits-vacancy-rate-drop)

[12] Justin B. Hollander, Karina Pallagst, Terry Schwarz, Frank J. Popper. 2010. “Planning Shrinking Cities.” Progress in Planning, Vol. 72, No. 4, pp. 223-232.

[13] Kim Kisner. 2022. “The What, When, Where and Why of Greenways in Detroit.” DetroitIsIt Retrieved from: (https://detroitisit.com/the-what-when-where-and-why-of-greenways-in-detroit/)

[14] Press Release. 2022. “Michigan Central Advances Plans for Mobility Innovation District; Google Joins Ford as Founding Member; State of Michigan, City of Detroit Makes Critical New Commitments.” Michigan Central. Retrieved from: (https://michigancentral.com/michigan-central-advances-plans-for-mobilit…)

[15] Ruth Porat. 2022. “Investing in Detroit with Ford and Michigan Central.” Google Blogs. Retrieved from: (https://blog.google/outreach-initiatives/grow-with-google/michigan-central-ford/)