The Color of Inequality Part 4: Barriers to Sustainable Employment for Workers of Color

By: Mike Shields & Mohona Siddique

Date: June 4, 2020

AUTHORS' NOTE:

As the country was buckling under the weight of the COVID-19 pandemic, the widely broadcast killing of an unarmed Black man, George Floyd, by a white Minneapolis police officer along with Amy Cooper's threatening use of police force to confront Christian Cooper in Central Park added to a litany of events that precipitated renewed protests against police brutality across the nation. While some protests remained peaceful, like those in Camden, New Jersey, peaceful protests in Philadelphia incited civil unrest and resulted in violent confrontations. It is not the first time that communities in Philadelphia have protested against racial injustice and police brutality, and the events of recent weeks are not isolated. Rather, they exist within the historical context of the intersection of race and economic opportunity – and for Black Americans and many other communities of color in the U.S, economic opportunity and mobility still remain out of reach.

To provide context and data to inform ongoing conversations about structural racism and illustrate how these enduring inequalities have shaped present-day neighborhood and civic relations in Philadelphia, the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia is launching a special Leading Indicator series called The Color of Inequality. The series will highlight measures of racial and ethnic inequality in the City of Philadelphia to contribute to ongoing conversations about racism and prejudice.

Color of Inequality Part 4: Barriers to Sustainable Employment for Workers of Color

In Philadelphia and across the country, race is too often a predictor of the scope and breadth of challenges people face when connecting to employment opportunities. Educational attainment, the digital divide, lack of access to reliable transportation, and barriers associated with a criminal record all disproportionately affect workers of color from building sustainable career pathways that build household and generational wealth. In this week’s Color of Inequality, we explore the systemic barriers people of color face when seeking sustainable employment and discuss best workforce practices that can help connect more individuals to career opportunities. Our Leading Indicator data brief shows how race-based inequalities manifest themselves in the present-day Philadelphia labor market.

Impact of Unequal Education

As discussed in last week’s Color of Inequality, access to quality primary and secondary education in Philadelphia is starkly unequal and racially segregated. Poor accessibility to early childhood education, paired with the defunding and criminalization of inner-city public schools, present barriers to educational attainment, which fall heaviest on the shoulders of students of color.

Though colleges and universities have made efforts to promote racial diversity on their campuses, many are still racially polarized and benefit from a legacy of white privilege. Mirroring trends in primary and secondary education, students of color tend to attend under-resourced institutions of higher education, further exacerbating the educational attainment gap with white students. The readings below shed more light on this issue:

- Selective colleges with better financial resources and higher future earnings are overrepresented by white students. Black students enroll at less selective institutions that tend to be more overcrowded and financially constrained.

- Black and Brown students are more likely to drop out of college before completing their degree than white students. Conversely, white students are more likely to progress and attain advanced degrees.

- Affirmative Action policies are disproportionately implemented across states, with some states preventing the legislation measures altogether. In some cases, these policies have not addressed the issues of personal trauma, family troubles, financial issues, culture shock that minority students face in predominantly white universities.

Racial Profiling in Hiring

Many people of color face additional obstacles while applying for employment opportunities. In the past 25 years, there has been little to no change in the hiring rate of Black or Brown applicants in the U.S. according to the Harvard Business Review [1]. Racial profiling in hiring practices manifests when employers refuse to interview or hire an applicant because of their race or ethnicity. This profiling often stems from the fact that most recruitment and hiring is being done by Non-Hispanic White individuals who have been shown to hire within their own homogenous professional networks or prioritize resumes with “white-sounding” names [2]. Since 1990, while applying for jobs with identical resumes, Non-Hispanic White applicants on average receive 36 percent more call-backs than Black applicants and 24 percent more than Latinx applicants [1]. Though discrimination in hiring practices is prohibited according to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, racial profiling within recruitment still exists and is difficult to weed out. More research and information on racial profiling in hiring practices can be found here:

- Taking Steps to Eliminate Racism in the Workplace

- The Ultimate Guide to Avoiding Racial Discrimination in Hiring

- Discrimination in the Job Market in the United States

(image from The New York Times)

Racial Barriers in the Workplace

Once in the workplace, workers of color still face a legacy of structural racism that poses obstacles for retention and advancement. From microaggressions to stark salary differences, workers of color are forced to confront an office culture that has been tailored to the white worker [3]. Salaries, for example, are often determined by an employee’s education and previous experience which—because of the aforementioned obstacles related to unequal education—keeps the salaries of workers of color lower than their Non-Hispanic White counterparts. In a previous Leading Indicator, we detailed how Black and Latinx male workers in Philadelphia earn approximately $0.72 and $0.57 respectively to every Non-Hispanic White male dollar earned; with Black and Latinx females making only $0.70 and $0.54, respectively. Additionally, the overrepresentation of Non-Hispanic White managers and executives makes it difficult for many professionals of color to advance in their organization or field. Without mentors who are aware of the obstacles and burdens disproportionately faced by professionals of color, advancement opportunities tend to funnel to white coworkers [4]. These are only a few of the examples of how embedded racism in workplace practices keeps many workers of color from building sustainable career pathways. More resources on structural racism in the workplace can be found here:

The “Diversity Check-Box”

Campaigns to hire or recruit “more diverse” workers or leaders can also come from a place of structural racism in the form of tokenism. Like a “check-box” on a form or survey, many organizations ambitiously hire or recruit professionals of color for leadership positions or board membership for the purpose of seeming more diverse rather than actively utilizing the skills, talents, or perspective of professionals of color. As Kyana Wheeler of Seattle’s Race and Social Justice Initiative framed it, “Diversity is about numerical categorization” that some organizations pursue only to be more competitive for funding opportunities or to be better perceived by the public [5]. One only needs to see the current demographic makeup of board members and chairpersons among major companies. While the percentage of Black and Brown board seats among Fortune 100 companies has increased from 14.9 percent to 19.5 percent from 2004 to 2018, Non-Hispanic White individuals still represent 66 percent of all Fortune 500 board seats and 91 percent of their chairmanships [6]. This is not to say that all companies refrain from utilizing the experience and input of professionals of color in leadership roles, but the limited number of non-white leaders reflects a nominal commitment to inclusiveness and equity. Actively investing in and promoting professionals of color as equal decisionmakers within an organization's leadership can overcome the “diversity checkbox mentality” and open the organization to new ideas, perspectives, and profitable ventures. More information on the diversity checkbox and inclusiveness can be found here:

Leading Indicator – The Impact of Unequal Employment in Philadelphia

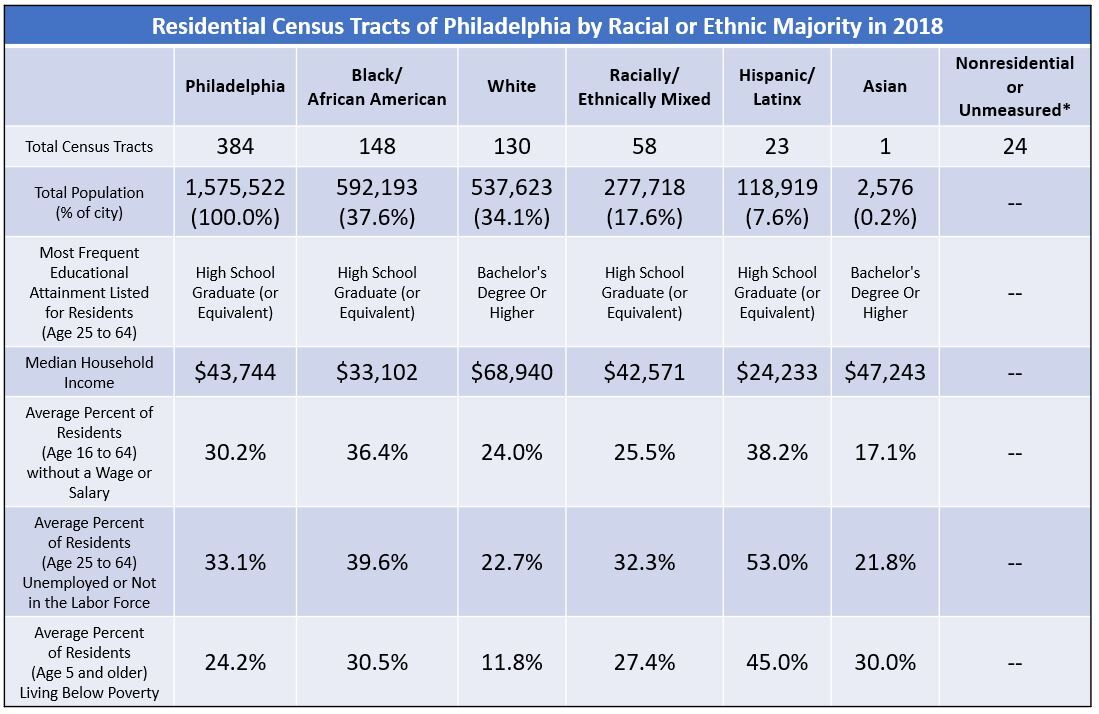

To illustrate the collective impact of barriers to sustainable employment opportunities and career advancement, Figure 1 shows a simplified spatial relationship between educational attainment, employment, income, wages, poverty, and race and ethnicity. Majority-Non-White tracts see lower educational attainment and greater unemployment levels than majority-Non-Hispanic-White tracts. This relationship correlates with decreased wages and household income and greater rates of poverty.

FIGURE 1

NOTE: Data were obtained from five-year estimates of the 2018 American Community Survey maintained and curated by the U.S. Census Bureau. Tracts were excluded from demographic measures if the population count was less than 500 residents or the "group quartering" population exceeded a third of residents.

The table in Figure 2 aggregates the measures of Figure 1 across census tracts by the racial or ethnic majority of their residents. It shows that majority-Black and majority-Latinx census tracts see the disproportionate impact of employment exclusion. Majority-Latinx tracts see the highest impact with 53 percent of working age residents unemployed or not in the labor force in 2018 – 1.3 times that of majority-Black tracts and 2.3 times that of majority-Non-Hispanic-White tracts. Additionally, majority-Latinx tracts see both the highest percentage of residents living in poverty (45.0%), the highest percent of working age residents without a wage or salary in 2018 (38.2%), and the lowest recorded median household income ($24,233). Majority-Black tracts do not fare much better, with 39.6 percent of residents unemployed or not in the labor force in 2018 – 1.7 times that of majority-Non-Hispanic-White tracts and 1.2 times that of the city as a whole. Similarly, majority-Black tracts have the second highest percentage of residents living in poverty (30.5%), the second highest percentage of residents without a wage or salary in 2018 (36.4%), and a median household income that is only 48 percent of majority-Non-Hispanic-White tracts ($33,102).

FIGURE 2

NOTE: Data were obtained from five-year estimates of the 2018 American Community Survey maintained and curated by the U.S. Census Bureau. Tracts were excluded from demographic measures if the population count was less than 500 residents or the "group quartering" population exceeded a third of residents.

In light of substantial barriers to sustainable employment and career advancement, it is important for policymakers to fund programs that give communities of color better access and training for today’s labor market. Workforce development programming like that of the Lenfest North Philadelphia Workforce Initiative and the West Philadelphia Skills Initiative are vital interventions for populations that face a legacy of structural exclusion from quality jobs with career pathways. You can read about equitable practices for sustainable employment in light of the COVID-19 crisis, and see below for some best practices for addressing sustainable employment barriers.

Employer Engagement

Early and continual engagement between workforce development providers and employers yields effective results for job seekers, employees, and employers. Among many positive outcomes, employer engagement can help align workforce development training programs with employer needs, making it easier for participants to secure employment [7]. The most successful examples of employer engagement include robust partnership providers as well as continued investment of monies and resources to make public investments in workforce programs go further [8]. Employer engagement can take many additional forms, including co-development of training curricula with workforce development service providers; developing continuing education and creation of training, credentials and support services that help employees advance along career pathways.

Community Engagement

When workforce development providers and employers tap into existing civic infrastructure and community networks, it can help facilitate employer connections, disseminate relevant training opportunities, and connect individuals to the right resources [9]. For traditionally underserved communities where employment and advancement opportunities are limited, and where there is a lack of access to information and resources, comprehensive community engagement can help close the gap by directing individuals to the right resources.

Career Advancement

Programs that take a career advancement approach create strong cohesion between stakeholders, employers, jobseekers, and employees [10]. Sometimes known as “career pathways,” career advancement clearly articulates routes to well-paying jobs and provides support and guidance to individuals moving along the path. Individuals gain specific skillsets and achieve progressive levels of education and credentials that lead to a better job. Well-designed career advancement opportunities are flexible, with multiple entry and exit points to meet the needs of individuals with different skill levels, career goals, and changing family or other personal responsibilities. A workforce development ecosystem built on principles of career advancement typically offer continual learning opportunities and corresponding wage growth, leading to positive outcomes for workers and for employers [8].

Sharing of Resources and Information

An interconnected workforce development ecosystem begins with individual workforce development programs’ ability to collect and share valuable information and resources [8]. Whether it’s publishing retention and matriculation data, distributing information about program start dates, or sharing training details, sharing resources and information serves an important purpose: it better educates providers to the breadth of resources available at peer institutions, and how those resources are used. This dynamic facilitates warm handoffs between programs, and proactively allows for job seekers to connect to resources that are the best fit for their needs.

Broad Access to Supportive Services

Services such as childcare, transportation, digital resources, physical and mental healthcare, among many others, are all independently linked to advancing job training and workforce development outcomes [11,12]. Similarly, lack of access to these resources can have negative workforce-related consequences. This report refers to these resources as “supportive services.” These supportive services fall outside of what may traditionally be thought of as workforce development but are nevertheless central to how and where individuals engage with the workforce. When individuals have access to the supportive services they need, like affordable childcare or reliable transportation services, they experience fewer roadblocks to finding and maintaining employment. Supportive services also extend to an individual’s health and mental health wellness—factors that can deeply impact one’s ability to find and keep employment.

Works Cited

[1] Quillian, Lincoln, Devah Pager, Arnfinn H. Midtbøen, & Ole Hexel. 2017. “Hiring Discrimination Against Black Americans Hasn’t Declined in 25 Years.” Harvard Business Review, October 11. Retrieved from: (https://hbr.org/2017/10/hiring-discrimination-against-black-americans-h…).

[2] Gerdeman, Dina. 2017. “Minorities Who 'Whiten' Job Resumes Get More Interviews.” Working Knowledge: Business Research for Business Leaders, May 17. Retrieved from: (https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/minorities-who-whiten-job-resumes-get-more-i…).

[3] Gray, Aysa. 2019. “The Bias of ‘Professionalism’ Standards.” Stanford Social Innovation Review, June 4. Retrieved from: (https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_bias_of_professionalism_standards).

[4] Center for Talent Innovation. 2019. Being Black in Corporate America: An Intersectional Study. New York City, NY: Center for Talent Innovation. Retrieved from: (https://www.talentinnovation.org/Research-and-Insights/).

[5] Avins, Jenni. 2020. “How to Build an Actively Anti-Racist Company. Quartz, June 4. Retrieved from: (https://qz.com/work/1864529/how-to-build-an-actively-anti-racist-workpl…).

[6] DeHaas, Deb, Linda Akutagawa, & Skip Spriggs. 2019. “Missing Pieces Report: The 2018 Board Diversity Census of Women and Minorities on Fortune 500 Boards.” Deloitte LLP. Retrieved from: (https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/center-for-board-effectiveness/ar…).

[7] Spaulding, Shayne & Ananda Martin-Caughey. 2015. The Goals and Dimensions of Employer Engagement in Workforce Development Programs. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute. Retrieved from: (https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/76286/2000552-the…).

[8] Frontino, Nick, and John Taylor. 2017. Philadelphia Career Pathways Assessment. Philadelphia, PA: The Economy League of Greater Philadelphia. Retrieved from: (http://www.economyleague.org/uploads/files/647833388649500484-philadelp…).

[9] Spaulding, Shayne & David C. Blount. 2018. Employer Engagement by Community-Based Organizations: Meeting the Needs of Job Seekers with Barriers to Success in the Labor Market. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute. Retrieved from: (https://www.urban.org/research/publication/employer-engagement-communit…).

[10] Alliance for Quality Career Pathways. 2014. Shared Visions, Strong Systems. Washington, D.C.: The Center for Law and Social Policy. Retrieved from: (https://www.clasp.org/publications/report/brief/shared-vision-strong-sy…).

[11] Kyle Demaria. 2018. Getting to Work on Time: Public Transit and Job Access in Northeastern Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, PA: The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. Retrieved from: (https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/community-development/publicati…).

[12] Spaulding, Shayne & Semha Gebrekristos. 2018. Family-Centered Approaches to Workforce Program Services: Findings from Workforce Development Boards. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute. Retrieved from: (https://www.urban.org/research/publication/family-centered-approaches-w…).