Education & Innovation in Massachusetts

Next month, more than 100 business, civic and government leaders will travel to Boston as part of our Greater Philadelphia Leadership Exchange. As we prepare for the visit, we take a closer look at how Boston is tackling critical issues related to growth and opportunity. This piece focuses on the progress their region has made on education and talent development– from statewide efforts to reform both the k-12 education and community college system to Boston’s investments in significantly expanding access to quality early childhood education.

Greater Boston and Massachusetts have a long history of innovation in education -- from the founding of the first publicly funded school system in the US to creating grade levels and common standards that are the basis of our current education system to helping to build world class institutions of higher education. Today, the state and region continue to focus on systemic change and improvements along the education continuum.

The most prominent recent success story has been statewide K-12 reforms that propelled Massachusetts students to the top of national and global rankings. Beyond the K-12 work, the Greater Boston region and the state have undertaken exciting efforts to expand access to early learning and strengthen community colleges.

K-12 EDUCATION REFORM: A STORY OF SUCCESS

Since 2005, Massachusetts’ students have led the nation in reading and math performance on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) test, the largest nationally representative, ongoing assessment of American students. Globally, Massachusetts students score at or near the top on international science tests. And within the state, SAT scores have risen for 13 consecutive years and state standardized test results have improved consistently and dramatically over the last 20 years. How has Massachusetts achieved this? Leaders in the state point primarily to significant education measures in the Massachusetts Education Reform Act of 1993.

Bringing About Reform

1993 saw the convergence of two key events that had been in the making for some time – the resolution of an education funding lawsuit that dated back to 1978 and the passage of education reform legislation that was based on work begun in the late 1980s.

While students in Massachusetts were, on average, doing as well their peers across the US, the state faced challenges, particularly around funding. Low levels of state education funding coupled with limits on property taxes enacted in 1980’s Proposition 2 ½ made it extremely difficult for communities, especially lower-income ones, to adequately fund education.

As communities struggled, a lawsuit was making its way through the Massachusetts courts regarding adequate and equitable education funding. In 1993, in McDuffy v. Robertson, the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled that the state had failed to meet its constitutional duty to provide an adequate education to all public school children due to vast spending disparities between the state’s wealthiest and poorest communities. How the state should address these disparities was left up to the legislature and administration.

And around the same time the court issued this ruling, the state legislature and other stakeholders were, in fact, working on school reform legislation that would go beyond funding changes and drastically alter the state’s education landscape.

The legislative reform efforts were driven in large part by strong leadership from the business community. In 1991, the Massachusetts Business Alliance for Education (MBAE) published “Every Child a Winner,” which became the template for reform. The report laid out what is referred to as the “grand bargain” – more resources for schools along with more accountability. The report went into great detail around funding, including a costing-out study to determine how much districts needed to educate children and proposing a state finance system to provide districts with adequate, equitable, and stable funding. To improve parity, the formula took into account a community’s ability to locally raise funds and the need for additional resources to serve at-risk students.

Following the release of the report, business, education, and state and local government leaders worked together to draft and advocate for a comprehensive standards-based bill that ultimately became the Massachusetts Education Reform Act of 1993 (MERA).

What the MA Education Reform Act Did

MERA was a complex piece of legislation that ushered in many changes, the most significant among them:

A substantial increase in state funding for education, particularly for low-spending districts; A clear curriculum framework laying out what students were expected to learn; and A standard assessment system, known as the MCAS, to track progress and ensure the reforms were effective.

MERA doubled the state’s investment in schools. This additional money, along with a new funding formula, decreased the disparities between high- and low-spending districts. Equally important, MERA created the first-ever statewide academic standards and aligned them with standardized tests, the MCAS, which provided data on individual students, classes, and schools.

Beginning with the Class of 2003, students were required to pass the 10th grade MCAS tests in order to graduate. Those involved in implementation of reforms point to this as the singular goal that drove reform efforts and kept everyone focused on a shared objective.

Among the systems reforms were an end to school principal tenure, redefined roles of School Committees (school boards), and allowing charter schools to be established. The first charter opened in 1995, and just over 100 charters operate in the state currently, the majority in urban districts (including 25 in Boston).

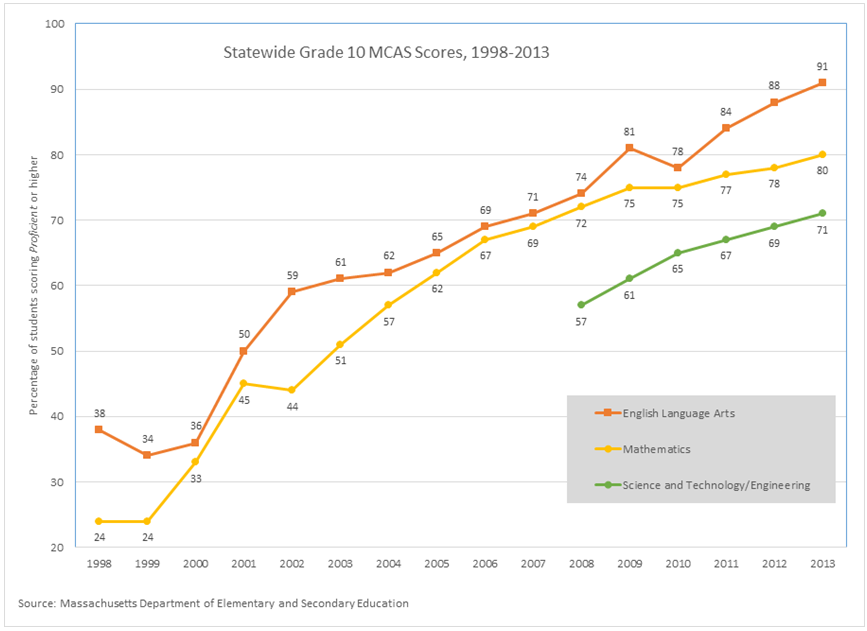

As the figure shows, the results of these reforms have been staggering. In 2013, 91% of 10th graders scored at a proficient level on the reading portion of the MCAS and 80 percent on the math portion.

The Secrets to Success

In developing the “Every Child a Winner” report, MBAE worked closely with a diverse group of stakeholders including union leaders, individual teachers and principals, school boards, superintendents, philanthropic foundations, education advocates, and policy experts, asking each group to bring their expertise to help find solutions. This approach was instrumental in the success of reform, and is apparent in the tone of the MBAE report, which explicitly address the historic rift among these groups, but especially between the education and business communities. Although the report went into great detail on funding, recommendations related to schools and systems change were broad and focused on the need to measure progress. The specifics were left up to “professionals within the system.”

While there were challenges and disagreements among stakeholders, those driving reform were able to keep all these parties at the table, advocating for reform throughout the process.

Remaining Challenges

While the Massachusetts approach to reform and impressive achievements have provided a model for improving schools, real challenges remain. High test scores are based on averages that mask significant disparities, and Massachusetts has some of the largest achievement gaps among states for black, Hispanic, and low-income students as measured by test scores and graduation rates. In addition, the long-running gains in test scores have recently stalled, in some cases, even began to decline. And while the state continues to lead the nation in student performance, a number of other states are making rapid gains and closing in on Massachusetts.

Many point to funding challenges and a persistent gap between low- and high-spending districts as the cause of stalled achievement. In fact, a Boston Foundation report commissioned by the MBAE found that the gains made in equalizing spending through the early 2000s have been nearly wiped out by losses in the years since due to flat funding and increased costs of health care and other budget items not related to student instruction.

Beyond funding, many policy experts argue that “more of the same” won’t be sufficient to close persistent achievement gaps and further increase test scores. Still, leaders are hopeful -

“We should at this point, in this state, have enough social capital built up and enough respect for all of our commitment to this effort that it should allow for a much different next phase of reform, a phase that’s more focused on where there is consensus related to real change and improvement, less wariness and skepticism about motivations, and that ought to help us to move faster.” - Tripp Jones, Managing Director, New Profit, Inc.

An additional challenge is momentum. Leaders are struggling against the attitude that education reform is “done.” The state has improved the funding situation and student achievement is, on average, quite good, so there is no sense of urgency.

In spite of this, the MBAE and others continue their work. MBAE is currently working on a new reform agenda focused on improving the quality of instruction and school leadership.

Individual districts are trying new tactics to improve student outcomes. In Boston, charter schools have made exceptional progress, and in partnership with the teachers’ union and others, new school models have been developed that provide leaders with more autonomy in hiring, budgeting, and curricula in an effort to boost achievement.

BOSTON PUBLIC SCHOOL PRESCHOOL PROGRAM

One of the few areas of education where the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has not led the US is in public preschool. Across the state, 4% of 3 year-olds and 14 percent of 4 year-olds are in publicly funded pre-k programs, putting them middle of the pack in comparison to other states.

In the face of slow progress at the state level, the City of Boston, like a number of other cities (San Antonio, Denver, New York City) has put resources toward expanding pre-k. In 2005, Boston Mayor Tom Menino set the goal of serving all 4 year-olds in Boston in full-day preschool by 2010. At that point, 750 children were enrolled. While the city hasn’t met Mayor Menino’s goal, it has made impressive gains in both the share of children served and the quality of programming. Approximately 2,200 (or 36%) 4 year-olds are currently served, and Menino’s successor, Mayor Martin Walsh has committed to doubling that number by 2018.

Unlike most public pre-k programs, Boston’s program has no income limits; however, around 64% of the children served are low-income, 40% have limited English proficiency, both of which increase a child’s risk of not having the skills and social competencies they need to thrive in kindergarten.

Mayor Walsh has appointed a Universal Pre-K Advisory Committee to look at issues including class space requirements, teacher qualifications, funding requirements, and potential partnerships for before school, after school, and summer wrap-around services.

As experts work on the practical and financial logistics of doubling the size of the program, they are also focused on maintaining the exceptional quality of the program. Research has confirmed that Boston Public Schools pre-k is having a significant impact on children’s language, literacy, and math skills as well as more modest effects related to executive functions including working memory and self-regulation. Researchers point to the developmentally appropriate, evidence-based curricula and highly-trained (and well-paid) teachers. Preschool teachers in the program earn the same salary as K-12 teachers, are required to have a master’s degree within five years of being hired, and receive ongoing professional development.

To date, all preschool programming has been provided in public schools in the city. Large-scale programs typically use a mixed-service delivery model, with accredited private centers providing services in addition to public schools. This is often a practical (need for space) as well as philosophical (avoiding competition between private providers and the state) decision. As Boston looks to expand, they, too, are planning to allow private centers to provide public preschool programs.

RETHINKING COMMUNITY COLLEGES

While Massachusetts’ community colleges have not been considered national leaders, recent efforts to reform the 15-college system has attracted attention. In 2011, Governor Deval Patrick signed legislation that dramatically changed the way community colleges are governed and standardized coursework across the system. Most impressively, the legislation enacted performance-based funding. These changes provided a vision of a more responsive system to both student and employer needs in an effort to better prepare graduates for well-paying jobs in the state. While there were several factors leading to the reforms, key events included the creation of the Vision Project and a Boston Foundation report.

In both Massachusetts and nationwide, community colleges struggle with low completion rates, lack of alignment between curricula and employer needs, and declining public investment. To address these issues, the state’s Commissioner of Higher Education, Richard Freeland, introduced the Vision Project in 2011. The Project aimed “to produce the best-educated citizenry and workforce in the nation” through initiatives focusing on college participation, college completion and workforce alignment.

Later that year, the Boston Foundation released a report that shed light on a number of significant problems with the Commonwealth's system. Most strikingly, the authors noted that while average tuition costs in Massachusetts were significantly higher than the national average, completion rates were significantly lower. While they applauded efforts of the Vision Project, the authors contended that its goals could not be realized without system-wide reforms designed to bring the largely autonomous group of 15 schools under greater alignment though state oversight.

The authors argued that the lack of a unified system had practical implications for students and employers; for example, the lack of standardized course numbers and degrees made transferring difficult for students and employers did not have a clear understanding of what skills to expect of degree- or certificate-holders. The report also highlighted the state’s outdated funding formula, which provided only incremental, across-the-board percentage increases or reductions rather than taking performance, program costs, or student enrollment into account.

The report provided a comprehensive set of recommendations to address these issues, which were backed by Governor Patrick. He issued a clear call to action in his State of the Commonwealth address the following January: “[Community colleges] must be aligned with employers, voc-tech schools and Workforce Investment Boards in the regions where they operate; aligned with each other in core course offerings; and aligned with the Commonwealth’s job growth strategy. We can’t do that if 15 different campuses have 15 different strategies. We need to do this together. We need a unified community college system in Massachusetts." He noted that successfully implementing these reforms would ultimately yield numerous benefits to the state -- particularly given that 90% of community college graduates stay in the state once they complete their postsecondary credential.

Following the Governor's address, a group of civic, community, and business leaders coalesced to support his proposal – citing the success of similar efforts to advance legislative reform related to K-12 education. The group, called the Coalition for Community Colleges, was made up of key players such as the Boston Foundation, the Massachusetts Competitive Partnership (a powerful business organization representing many of the Commonwealth’s largest employers), and dozens of other groups.

Despite mounting support for the reforms, a number of community college presidents firmly opposed them, citing concerns that centralization would take away their ability to quickly adjust curricula to meet local employer needs and eliminate successful programs in the name of standardization. Regardless, the bill passed with strong bi-partisan support in June 2012.

The bill made a number of big changes to the way colleges are governed, including giving the state's Board of Higher Education powered to appoint and remove college presidents and greater oversight in the staffing of senior management positions; in addition, the governor was granted the authority to appoint the Chairman of each community college’s board of trustees. Most importantly, it called on the Commissioner of Higher Education to develop a revamped performance-based funding formula for all 15 colleges.

The colleges piloted this new funding structure in 2014. Unlike many other performance-based payment systems, which critics often argue encourage service providers to recruit those who can be served most easily, the Massachusetts model provides incentives to both retain and graduate at-risk students. And, to further promote alignment with the state's economic development priorities and employer needs, the formula also provides additional funds when students graduate with certificates or degrees in high-demand industries.

To give colleges time to adapt, the state phased in the new funding model. Until 2017 all colleges will receive “stop-loss” funding. Beginning in 2017, each school will receive a base operating subsidy and the remaining funds will be awarded based on two factors: size and course credit hours, and performance (with incentives for alignment with the state’s Vision Project). With 50% of each college’s funding based on performance, Massachusetts will have one of the most progressive formulas in the country.

Initial feedback from colleges on the new funding model has been relatively positive, but the challenge of ensuring access for all still lies ahead. “It’s a move in the right direction that there’s more funding being directed to community college students…but we still have some distance to cover increasing funding to public higher education,” Cape Cod Community College President John Cox suggests.

Looking ahead, in 2016, a similar performance-based funding formula is to be developed for the state university system.