The Impact of COVID-19 on Greater Philadelphia’s Black-Owned Businesses

The economic lockdown in response to the COVID-19 pandemic is entering its fifth month. Businesses of all sizes are reeling from its effects. While some have been able to take advantage of federal, state, and local cash relief programs, many have been forced to close their doors forever. In fact, minority-owned businesses—and Black-owned businesses in particular—are reporting a greater risk of closing than their white-owned counterparts. In this Leading Indicator, we dive deeper into the metro area’s Black-owned businesses to learn more about the status of race relations and equitable opportunity in our region.

Key Takeaways

- In 2017, 20.3 percent of Greater Philadelphia’s population identified as Non-Hispanic Black, but only 2.5 percent of all employer firms were Non-Hispanic-Black-owned.

- The City of Philadelphia had the highest rate of Black-owned employer firms in the region in 2017 at 5.4 percent; even though Non-Hispanic Black residents made up 41.3 percent of the population in 2017.

- Regional Black-owned businesses show higher than average concentrations in the health care and social assistance industry, the transportation and warehousing industry, the administrative support and waste management industry, educational services, and the arts and entertainment industry.

- Researchers have estimated that roughly 40 percent of Black-owned businesses nationally have closed due to the pandemic-induced recession; others predict up to a 60 percent attrition rate.

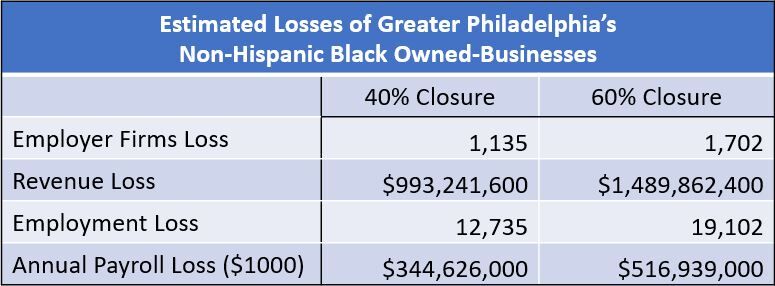

- In our region, a 40 percent attrition rate among Black-owned businesses would equate to a loss of 1,135 firms, $993 million in regional revenue, 12,735 jobs, and $345 million in wages

- A 60 percent attrition rate would equate to the loss of 1,702 firms, $1.5 billion in regional revenue, 19,102 jobs, and $517 million in wages

The State of Black-Owned Businesses Amid the Pandemic

In 2017, Non-Hispanic Blacks made up 12.3 percent of the total U.S. population, yet only 2.2 percent of all U.S. firms were recorded as Black-owned [1,2]. This disproportionately small representation stems from a legacy of structural racism that continually prevents many Black entrepreneurs from fully accessing investment resources and business support. Many Black-owned businesses start out in a higher state of fiscal vulnerability than businesses owned by other racial and ethnic groups [3]. In fact, a recent report by McKinsey & Company detailed how 57 percent of Non-Hispanic Black-owned businesses were labeled as having poor financial health when using traditional lender requirements liked sustained profits, “good” credit, and external funding [4]. As Brookings Fellow, Andre Perry, notes, Black businesses have traditionally been denied financial investments in ways that have throttled generational wealth creation in Black communities [5].

The pandemic has served to exacerbate these structural inequalities affecting Black business ownership. Since the lockdown’s onset, Black-owned businesses have been impeded from accessing cash relief programs—like the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP)—because of the ways in which these programs rely on existing banking. They also privilege firms with employees over sole proprietorships, which make up the vast majority of Black-owned firms in the U.S. Yet, even Black-owned firms with employees faced barriers to access; reports have shown that qualified minority-owned businesses were less likely to be approved for loans than white-owned businesses [3]. As of April 2020, 40 percent of Black business owners reported that they were not working compared to only 17 percent of white business owners [6]. It seems highly likely that the pandemic has only amplified existing inequities for Black business owners.

Greater Philadelphia’s Black-Owned Businesses

Mirroring the nation, the proportion of Black-owned businesses in the Greater Philadelphia region is disproportionately low. In 2017, 20.3 percent of the region’s population identified as Non-Hispanic Black, but only 2.5 percent of all employer firms were Non-Hispanic-Black-owned [1,2]. These firms generated $2.5 billion in revenue (0.3% of the total revenue generated in Greater Philadelphia), employed approximately 31,837 individuals (1.1% of Greater Philadelphia’s 2017 total nonfarm employment), and generated $862 million in annual payroll (accounting for 0.6% of Greater Philadelphia’s total annual payroll) [2,7]. It should be noted, however, that these data—from the U.S. Census—includes only businesses with employees and payrolls. It fails to account for sole proprietors like caterers, artists, daycare providers, construction workers, or other gig economy businesses. According to Pew, accounting for sole proprietors pushes Greater Philadelphia’s Non-Hispanic Black-owned business representation closer to 25.1 percent [8].

Figure 1 shows the distribution of Black-owned businesses across the eleven counties of Greater Philadelphia. Unsurprisingly, Philadelphia County is home to the greatest concentration of Non-Hispanic Black residents (41.0%) and the greatest representation of Black-owned employer firms (5.4%). The surrounding counties host much smaller proportions of Non-Hispanic Black residents and a commensurately smaller number of Black-owned businesses. In fact, there are so few Black-owned employer firms in Bucks County, PA, Gloucester County, NJ, Salem County, NJ, and Cecil, MD that the U.S. Census cannot share its estimates without risking deidentification.

FIGURE 1

NOTE: Data for Figure 1 were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau & the National Science Foundation's National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics’ 2018 Annual Business Survey and the U.S. Census’ 2014-2018 American Community Survey Five-Year Estimates.

While the region’s official count of Black-owned businesses remains disproportionately low, a deeper look shows some key differences within the concentrations across industry sectors. Figure 2 uses regional Census estimates to show the concentration of Black-owned employer firms (including those of Hispanic ethnicity) by industry. While Black-owned businesses constitute 2.7 percent of the region’s total employer firms, their concentration in health care and social assistance, transportation and warehousing, administrative support and waste management, educational services, and arts and entertainment far outpaces the regional average. Black-owned businesses also show a higher than average concentration in “other services” which includes repair and maintenance businesses, personal and laundry services, and religious and civic service organizations.

FIGURE 2

NOTE: Data for Figure 2 were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau & the National Science Foundation's National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics’ 2018 Annual Business Survey. Industries with less than 0.01 percent representation were not included.

Black-owned business representation in the health care and social assistance industry is more than double the concentration of the next highest transportation and warehousing industry. The health care and social assistance industry includes home and community care establishments, elderly care facilities, daycare services, recreation and fitness facilities, counseling offices, and social and community assistance establishments among many other businesses. We have previously detailed how Black Philadelphians show above average employment in this sector, so it is not surprising to see that many Black entrepreneurs are also providing goods and services in this industry.

There is a disproportionately lower concentration of Black-owned businesses among higher-paying segments of the service sector in industries like finance and insurance, information, and professional, scientific, and technical services. The Economy League has previously documented the need for more concerted efforts to attract and train women and people of color in STEM positions. New firms in these sectors often emerge from employees of existing firms. The small representation of Black-owned businesses in these profitable, tech-dominated service industries demonstrates the need for more regional investment and promotion of non-white and non-male businesses in STEM fields.

Closure of the Region’s Black-Owned Businesses

With numerous reports and news stories detailing the disproportionate effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black-owned businesses, we set out to understand the impact of their actual or potential closure on the Greater Philadelphia economy. Business closures equate to a loss of services, revenue, jobs, and wages. The loss of these financial assets ripple through the local economy by slowing the consumption of goods and services and diminishing local tax revenues. While normal business and job churn is healthy for a local economy, the loss of hundreds or thousands of businesses and jobs in a short period can deal a stinging blow that will take years—or even decades—to recover.

To illustrate the impact of business closures, we used closure estimates suggested by the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) and financial health estimates from the McKinsey & Company report on minority-owned businesses to approximate the effects of a 40 and 60 percent firm closure rate among the region’s Black-owned businesses (see Figure 3). These closure rates provide best-and-worst-case scenarios based on national trends.

FIGURE 3

NOTE: Data for Figure 3 were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau & the National Science Foundation's National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics’ 2018 Annual Business Survey.

Figure 3 shows that a 40 percent business closure rate among the region’s Black-owned businesses—roughly equivalent to the 41 percent closure rate suggested by SIEPR—would mean a loss of 1,135 firms, $993 million in revenue, 12,735 jobs, and $345 million in wages. A 60 percent closure rate—closely resembling the 57 percent of Black-owned businesses outlined by McKinsey & Company as “at-risk” or “distressed” prior to the pandemic—would equate to 1,702 firms lost, a loss of $1.5 billion in revenue, 19,102 jobs lost, and $517 million lost in wages.

Conclusion

As local policymakers, business leaders, and development experts continue to debate the economic ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic, minority-owned businesses and their impact on the local economy deserve far more attention, especially in light of the resurgent movements for racial equity.

In times of added distress and trouble, Black communities have had to focus inward and rely on their communities’ social capital. The power of this social capital within Black communities is often an overlooked strength that has led to numerous successes in places often bereft of the resources enjoyed by white communities. One such example comes from 91 Black-owned businesses within the Traffic Sales and Profit network (TSP), a purpose-driven Facebook group of Black entrepreneurs, who were able to generate $49 million in sales from July 2019 to July 2020. Most of these profits were earned during the pandemic [9]. Through mentorship, solidarity, and open communication these businesses were able to buck the prevailing trends of Black businesses closing during the economic lockdown and prove that Black businesses are adaptable and profitable when given proper attention and investment. With more hyper-local strategies working to invest in local Black businesses, Greater Philadelphia could also be a success story where equitable opportunity flourishes.

Works Cited

[1] U.S. Census Bureau. 2018. 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. Retrieved from: (https://www.census.gov/data.html).

[2] U.S. Census Bureau & the National Science Foundation's National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2020. The 2018 Annual Business Survey. Retrieved from: (https://www.census.gov/data.html).

[3] Flitter, Emily. 2020. “Few Minority-Owned Businesses Got Relief Loans They Asked For.” The New York Times, May 18. Retrieved from: (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/18/business/minority-businesses-coronavirus-loans.html).

[4] Dua, André, Deepa Mahajan, Ingrid Millan, & Shelley Stewart. 2020. “COVID-19’s effect on minority-owned small businesses in the United States.” McKinsey Insights, May 27. Retrieved from: (https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/social-sector/our-insights/covid-19s-effect-on-minority-owned-small-businesses-in-the-united-states).

[5] Perry, Andre, Tynesia Boyea-Robinson, & David Harshbarger. 2020. “This Juneteenth, we should uplift America’s Black businesses.” Brookings, June 18. Retrieved from: (https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2020/06/18/this-juneteenth-we-should-uplift-americas-black-businesses/).

[6] Fairlie, Robert. 2020. The Impact of COVID-19 on Small Business Owners: Evidence of Early-Stage Losses From the April 2020 Current Population Survey. Stanford, CA: The Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. Retrieved from: (https://siepr.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/20-022.pdf).

[7] Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2020. Current Employment Statistics. Retrieved from: (https://www.bls.gov/data/).

[8] D’Onofrio, Michael. 2019. “Black-Owned Firms Make Up Larger Share of Philadelphia’s Businesses than Previously Reported. The Philadelphia Tribune, December 1. Retrieved from: (https://www.phillytrib.com/news/local_news/black-owned-firms-make-up-larger-share-of-philadelphia-s/article_be21b456-e6e8-5133-b676-126a21fe834e.html?fbclid=IwAR11sQzY-uFwa43pL52REv-oX52qEW0nAj9dyzWyHaIsj03XK-t-HSuD5N8).

[9] Ledbetter Candace. 2020. “These 91 Black-Owned Businesses Worked Together to Generate $49M in Sales in One Year.” BlackBusiness.com, July 24. Retrieved from: (https://www.blackbusiness.com/2020/07/91-black-owned-businesses-generate-49-million-in-sales-one-year.html).