Greater Philadelphia’s Public Transportation System and COVID-19 – PART 3

Throughout our transit-focused series, we’ve explored ridership trends in Greater Philadelphia and detailed the demographics and socioeconomic status of riders. In this final installment, we explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the region’s largest transportation authority—the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA)—and examine how SEPTA’s proposed service reductions would impact riders.

Key Takeaways

- Between March and May of 2020, SEPTA’s ridership across all modes declined by 92 percent.

- Essential workers, low-income commuters, and riders of color have relied on public transportation as their primary commuting means during the pandemic.

- As a result of the pandemic-induced economic lockdown, SEPTA faces a budget crisis: fiscal year 2020’s operating budget is 25.3 percent lower than the previous year.

- Considering its fiscal position, SEPTA has proposed a “doomsday” service reduction plan that would cut average weekday trolley boards by 95 percent and reduce average weekday rail and subway ridership by 20 to 30 percent.

- More support and organization among regional civic and business leaders who understand the important role public transit plays in the local economy can catalyze advocacy efforts and spur more investments towards ridership.

Ridership During a Pandemic

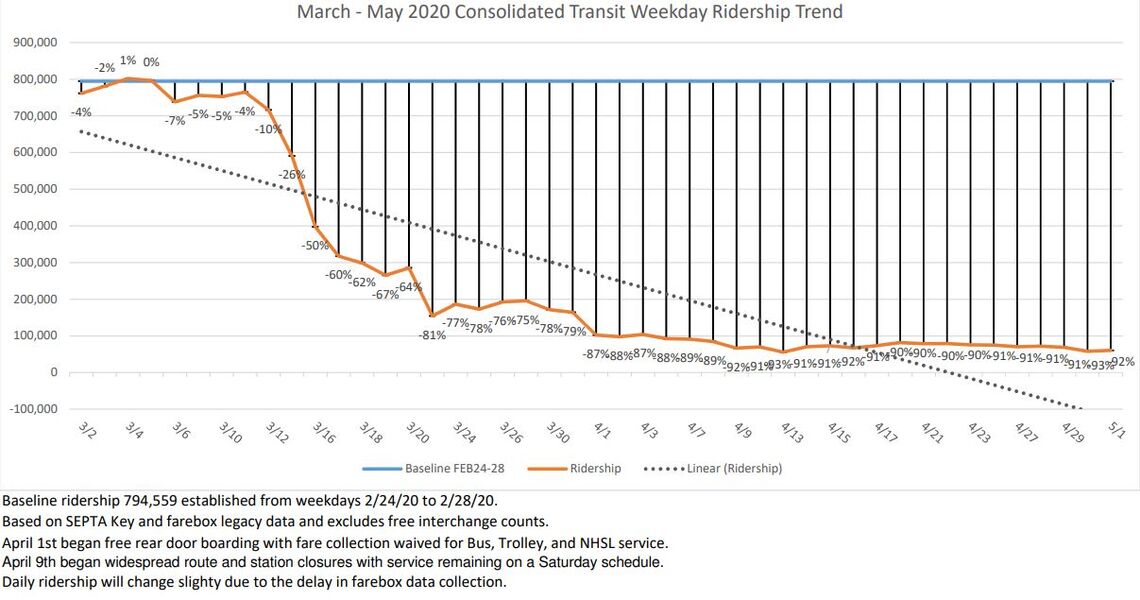

In January and February 2020 SEPTA’s ridership estimates were outpacing the previous year [1]. This changed dramatically with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic lockdown. Many businesses shuttered their offices and implemented work-from-home policies for non-essential workers to accommodate mandatory stay-at-home orders issued by Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf and Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney. With most of Greater Philadelphia’s workers staying at home, SEPTA’s ridership plummeted. Between March and May 2020, ridership across all modes declined by 92 percent. Figure 1 details this decline in weekday ridership across all modes.

FIGURE 1

SOURCE: SEPTA March through May 2020 Ridership Baseline Tracking

Of course, some commuters continued to use SEPTA’s transit services during the pandemic out of necessity. Many essential workers—specifically workers in healthcare, safety and emergency services, transportation and delivery services, and food-related distribution and retail—relied on transit services provided by SEPTA, PATCO, and Amtrak as their primary means of commuting during the pandemic. Our previous piece in this series demonstrated that city and suburban workers in the Education, Health Care, and Social Assistance industry had the highest representation among transit users prior to the pandemic. It is likely that many of these workers continue to use public transit. A recent national survey of riders conducted by the mobile app Transit found that 92 percent of their users who were still using public transit during the pandemic were primarily using it to commute to work; roughly 40 percent identified as working in either Healthcare Support or Food Preparation [2].

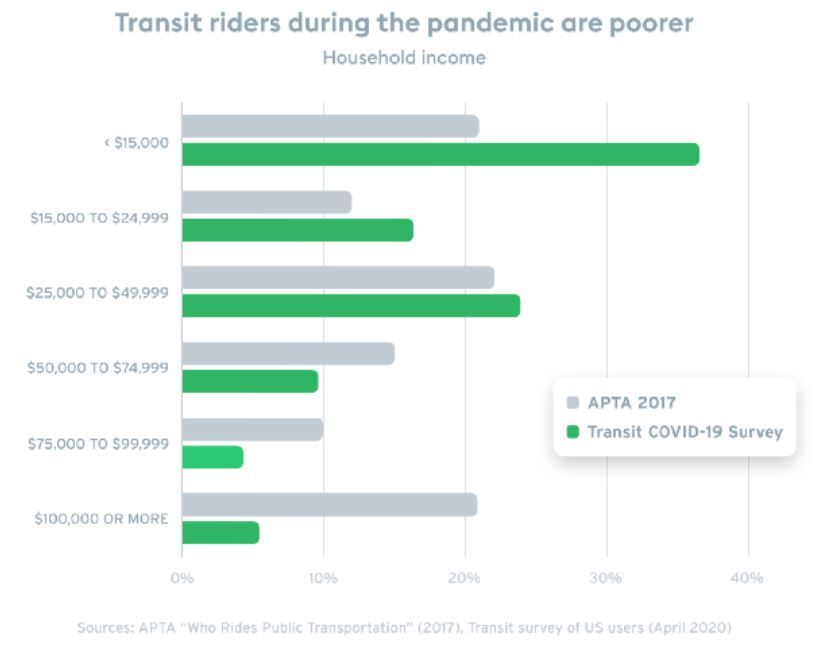

In addition to these essential workers, many low-income commuters have continued to use public transit during the pandemic. We previously detailed the correlation between poverty and public transit ridership in the region and how public transit is a lifeline for many poorer residents. Without access to personal vehicles, many lower-income individuals rely on public transit for commuting to work, grocery stores, pharmacies, and other health and social services. While demographic and socioeconomic data on Greater Philadelphia’s transit riders who have continued to utilize services during the pandemic is lacking, the Transit survey found more than 70 percent of their surveyed riders came from households that earned less than $50,000 a year [2]. Figure 2 details these findings with a 2017 comparative measure of public transit users.

FIGURE 2

SOURCE: “Who’s left riding public transit? A COVID data deep-dive.”

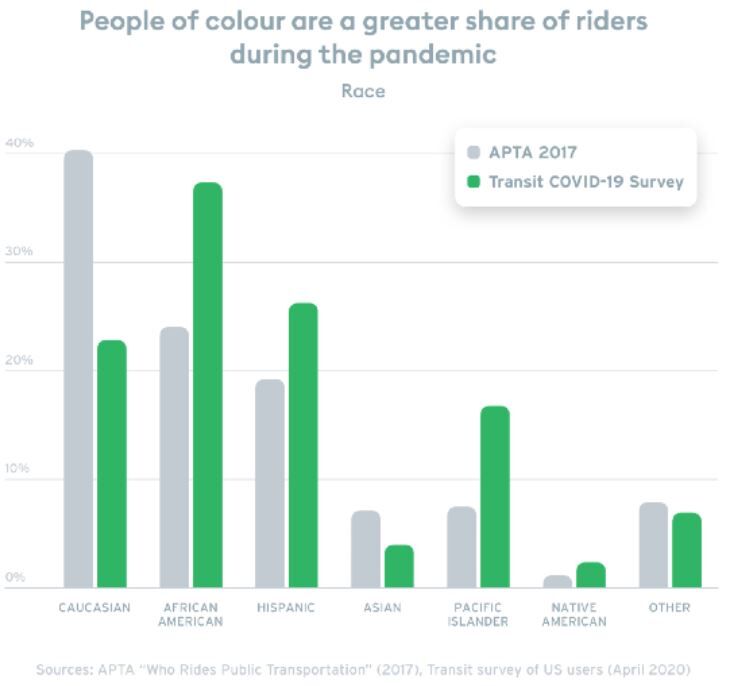

Because of poverty’s interrelationship with race and ethnicity in the U.S, it is no surprise that many individuals who continued to use public transportation during the pandemic also identified as a person of color. A recent study from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health and Boston University’s School of Public Health found that transit ridership among low-income people of color remained relatively stable since many worked in essential industries [3]. The Transit survey also found that the proportion of non-white public transit riders drastically increased during the pandemic, mainly due to steep drops in usage on the part of white riders (illustrated in Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

SOURCE: “Who’s left riding public transit? A COVID data deep-dive.”

Although SEPTA has seen a slight uptick in ridership after the initial declines in March and April 2020, it is unclear if ridership will reach pre-COVID levels within the next few years [1]. Even with $644 million received from federal CARES Act funding, SEPTA may still have to consider major service cuts to make ends meet [4].

COVID-19: Adding Insult to Injury for SEPTA’s Funding

SEPTA’s decline in ridership during the pandemic has had a significant impact on its operating budget. The budget for fiscal year 2020 was 25.3 percent lower than the previous year with ridership averaging about 35 percent its normal rate, and SEPTA expects a $400 million shortfall over the next three fiscal years because of the overall decline in riders’ fares [5,4].

In addition to this hit to the operating budget, SEPTA is facing a critical capital budget crisis. A large portion of SEPTA’s capital budget comes from toll revenues collected by the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission (PTC). A series of state legislative acts in 2007 and 2013 required the PTC to contribute $450 million annually to PennDOT to support state public transportation initiatives [6]. Not only has the pandemic sharply curtailed automobile travel on the turnpike and decreased toll revenues, but the PTC’s funding obligation is slated to drop to a $50 million annually in 2022, with the remaining $400 million to come from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s General Fund [7]. Without the guaranteed funds from PennDOT via the PTC, SEPTA faces a daunting capital funding challenge, pandemic notwithstanding.

In August, SEPTA’s General Manager, Leslie Richards, conveyed this dire funding situation to members of the Pennsylvania House Transportation Committee. As part of her testimony, she unveiled the worst-case scenario of proposed service cuts that would have to be made to match the decreased revenue. Figure 4 is an interactive version of this service reduction plan which illustrates which stations and lines would be cut from regular service if no funding can be made available. Stations colored red indicate rail, subway, or trolley stops that would no longer be in service (or replaced by bus services - in the case of the trolley lines). Additionally, spatial layers detailing estimates of public transit ridership among residents and the racial and ethnic majority population of each census tract are detailed for reference.

FIGURE 4

NOTE: Data were obtained from SEPTA’s GIS Data Portal, The Philadelphia Inquirer’s “SEPTA threatens to cut Regional Rail lines, pull back subway and trolleys in next decade if Harrisburg doesn’t boost funds” August 19 article, and five-year estimates of the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2014-2018 American Community Survey. Each racial majority group excludes individuals of Latinx/Hispanic ethnicity.

These service reductions will deeply impact the region’s poorer communities which rely most heavily on public transportation for their vital services. Of particular note are the various trolley and high-speed lines servicing large portions of low-income communities of color in Southwest Philadelphia, West Philadelphia, North Philadelphia, and Upper Darby. While the plan proposes to replace these lines with bus service, the change could leave these communities with limited transit service prone to additional delays, less reliable schedules, and more traffic congestion. Similarly, the reduction in service along the southern portion of the Broad Street subway line would leave many neighborhoods of South Philadelphia relying more heavily on bus transit to get to and from Center City. Finally, the reduction in regional rail stops would negatively impact many low-income neighborhoods in Northwest Philadelphia – like Germantown and Mount Airy—and close off service to many wealthier commuters along the Main Line, Doylestown, Downingtown, and in Northeast Philadelphia. Thus, without critical funding, SEPTA’s service reductions will negatively impact low income communities and cut services for wealthier communities that are more likely to contribute larger fare revenues.

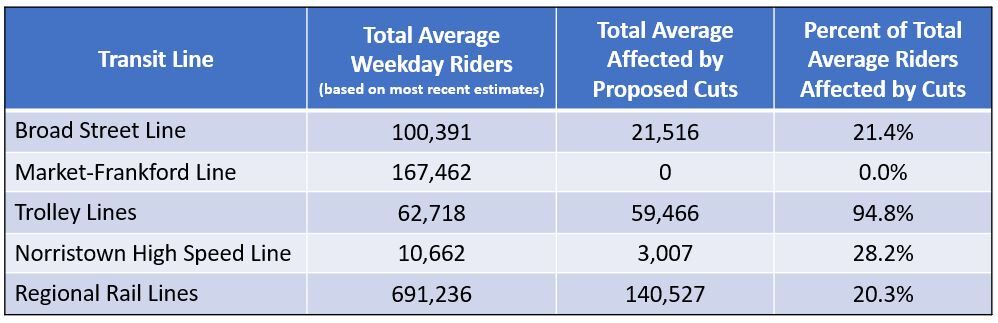

Figure 5 further details how these proposed service reductions would impact weekday ridership estimates across rail, subway, and trolley lines. Using total average ridership board counts from each station (from the most recent estimates available), figure 5 shows that almost 95 percent of weekday trolley ridership will be impacted by these proposed service reductions. Only the Market-Frankford subway line will remain at full capacity. The other rail and subway lines would see average weekday ridership decline by 20 to 30 percent.

FIGURE 5

SOURCE: SEPTA GIS Data Portal

NOTE: Broad Street Line ridership estimates come from FY 2017 turn-style counts and excludes free interchange riders. Market-Frankford Line ridership estimates come from FY 2017 turn-style counts and excludes free interchange riders. Trolley Stop ridership estimates come from Spring 2018 automatic passenger count data where available. Norristown High Speed ridership estimates come from Fall 2017 automatic passenger count data where available. Regional Rail ridership estimates come from SEPTA’s 2015 Regional Rail Census counts.

Public Transportation is an Economic Necessity

A strong public transportation system plays a major role in providing access to economic opportunity in a metropolitan area. The Economy League has written extensively on the vital role public transit plays in the region’s economy. A fully integrated multimodal transit system can help attract businesses to region, increase employment, pull families out of poverty, decrease pollution, and increase local tax revenue [8]. Public transportation also supports the “essential workforce” during times of economic and social upheaval. When looking towards Greater Philadelphia's immediate future and economic recovery, the local transit systems will be a key determinant of success.

For public transportation authorities like SEPTA to survive these trying times, they will need support from local civic and business leaders who understand the role public transit plays in the region’s economy and advocate for investment in the system. Transportation authorities also need the buy-in and support of the local citizenry who can organize and amplify the voices and ideas of public transit supporters in the Greater Philadelphia region. We hope, that with the formation of new coalitions like Transit Forward Philadelphia, that more residents will understand the pivotal role public transportation plays in the regional economy and will help strengthen the case to expand and improve our system to the benefit of people, communities, and businesses across the region.

Works Cited

[1] Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority. 2020. Revenue and Ridership Report: June and Fiscal Year-End 2020. Philadelphia, PA: Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority. Retrieved from: (http://septa.org/strategic-plan/pdf/R&RJun20.pdf).

[2] Transit. 2020. “Who’s left riding public transit? A COVID data deep-dive.” Medium, April 27. Retrieved from: (https://medium.com/transit-app/whos-left-riding-public-transit-hint-it-s-not-white-people-d43695b3974a).

[3] Mailman School of Public Health. 2020. “Subway Data Reveals Communities of Color Carry the Burden of Essential Work and COVID-19.” Columbia University, June 5. Retrieved from: (https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/public-health-now/news/subway-data-reveals-communities-color-carry-burden-essential-work-and-covid-19).

[4] Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority. 2020. Board Report: Selected Financial and Operating Performance Results June 2020. Philadelphia, PA: Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority. Retrieved from: (http://septa.org/strategic-plan/reports/12_June%202020.pdf).

[5] Madej, Patricia. 2020. “SEPTA, facing ‘devastating’ financial losses from coronavirus, highlights customer service tweaks to woo back riders.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, September 8. Retrieved from: (https://www.inquirer.com/transportation/septa-covid-19-recovery-plan-move-better-together-coronavirus-20200908.html).

[6] PA Mobility Partnerships. 2019. The Southeast Partnership for Mobility: Final Report. Harrisburg, PA: Retrieved from: (https://www.paturnpike.com/yourTurnpike/partnership_for_Mobility.aspx).

[7] Madej, Patricia. 2020. “SEPTA threatens to cut Regional Rail lines, pull back subway and trolleys in next decade if Harrisburg doesn’t boost funds.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 19. Retrieved from: (https://www.inquirer.com/transportation/septa-funding-regional-rail-subways-trolleys-turnpike-coronavirus-20200819.html).

[8] Weisbrod, Glen; Derek Cutler; & Chandler Duncan. 2014. Economic Impact of Public Transportation Investment, 2014 Update. Washington, DC: American Public Transportation Association. Retrieved from: (https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/Resources/resources/reportsandpublications/Documents/Economic-Impact-Public-Transportation-Investment-APTA.pdf).