COVID-19 and Greater Philadelphia’s Small Businesses

The mandated social distancing and closure of non-essential businesses in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have disproportionately affected the region’s small businesses. While larger enterprises have greater capacity to weather short term setbacks like sharp declines in revenue and layoffs, smaller businesses are typically less resilient. As the public health and economic lockdown seems likely to extend into the summer, many small enterprises will face bankruptcy and permanent closure. Since small businesses play a vital role in the Greater Philadelphia economy, mass small business closures could dramatically halt regional economic growth for quite some time. In this Leading Indicator, we explore the size and economic contribution of the regions’ small businesses.

Key Takeaways

- As of 2017, 99.7 percent of Greater Philadelphia’s businesses employed less than 500 people while 53.7 percent employed less than five people.

- More than a third of Greater Philadelphia’s industry sectors are dominated by small businesses with less than five employees.

- In 2013, there were roughly 27,000 small business establishments in the City of Philadelphia - employing the majority of the city’s workers, producing over $31 billion in payroll annually, and generating about $1.2 billion dollars in wage tax revenues.

- As the pandemic and subsequent economic lockdown continue, the mass effect of small business closures in Greater Philadelphia will have severe long-term economic effects.

What Makes a Business Small?

According to federal guidelines, a “small business” is as any establishment with less than 500 employees [1]. Small businesses tend to provide unique goods or services to localized clienteles of customers and other small and large businesses, and they tend to be rooted in place. They contribute both to the local economy and civic fabric of the towns or cities where they are located: adding to the tax base, providing employment opportunities, and promoting market diversity. They are also important parts of the supply chain, both as consumers and producers of goods and services for other establishments [2].

By sheer volume, small businesses dominate both the national and regional economy. As of 2017, over 99 percent of all business establishments in the U.S. as well as in the Philadelphia Metropolitan Region were small businesses. Figure 1 demonstrates the density of small businesses across Greater Philadelphia: while large employers account for only 0.3 percent of the region’s businesses, 53.7 percent of the region’s establishments employed less than five people.

FIGURE 1

NOTE: Data for Figure 1 were obtained from the U.S. Census’ 2017 Economic Annual Surveys; specifically, County Business Patterns by Legal Form of Organization and Employment Size Class for U.S., States, and Selected Geographies.

The high concentration of small businesses is reflected across all industries in the region as well. In fact, Figure 1 shows that more than a third of the region’s industries are dominated by establishments with less than five employees. Even the Educational Services and Health Care & Social Assistance sectors - where Philadelphia’s large “eds and meds” institutions are located - have relatively high concentrations of small businesses - often working in partnership with the region’s universities and hospitals.

The Economic Contribution of Small Businesses

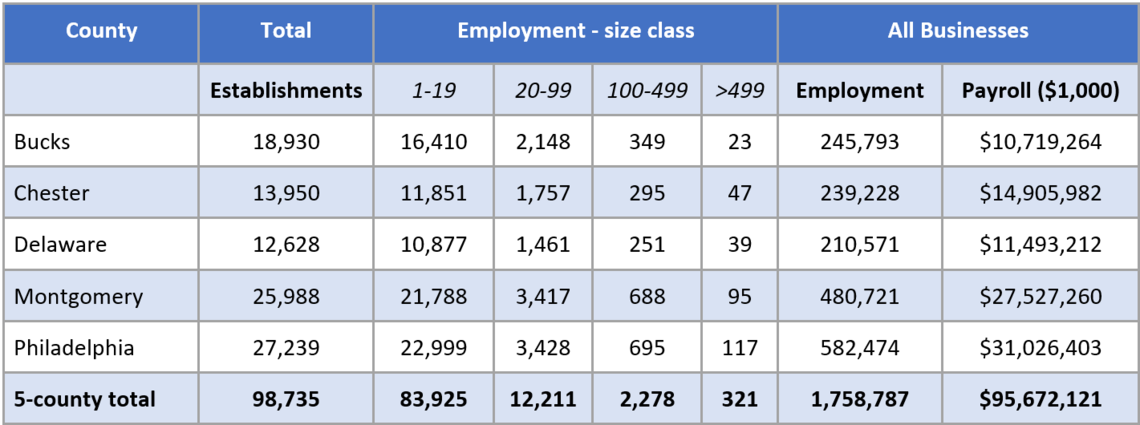

According to the Small Business Administration, small businesses accounted for two-thirds of net new jobs and roughly 43.5 percent of the national GDP (roughly $5.9 trillion in economic activity) in 2014 [3]. According to data from the Pennsylvania Small Business Development Centers, there were about 27,000 small business establishments in the City of Philadelphia in 2013 - employing the majority of the city’s workers, producing over $31 billion in payroll annually, and generating about $1.2 billion dollars in wage tax revenues [4]. Of these 27,000 small businesses, more than 95 percent had fewer than 100 employees and 83 percent had fewer than 20 employees. Figure 2 shows that there were roughly 99,000 small business establishments within the five counties that comprise Southeastern PA (SEPA) in 2013. Roughly 85 percent of these establishments employed fewer than 20 people and more than 97 percent employed fewer than 100 people. Combined payroll for small businesses in SEPA was $95.7 billion in 2013 [4]. In sum, small businesses are the lifeblood of both the national and the local economy.

FIGURE 2

NOTE: Data for Figure 2 were obtained from the Small Business Development Centers of Pennsylvania.

Ascertaining the regional economic contribution of small businesses by industry, however, is challenging due to data limitations. Figure 3 estimates the economic contribution of small businesses within the region’s major service-sector industries extrapolating from national estimates of small business GDP. While these numbers are only estimates, they demonstrate how much small businesses contribute to local industry outputs. In fact, the substantial contribution of small businesses to the Wholesale & Retail Trade industry’s gross receipts at $126 billion is astounding; this sector is truly dominated by small businesses.

FIGURE 3

NOTE: Data for Figure 3 are estimates of small business economic contribution using national estimates of small business GDP contributions from Kathryn Kobe and Richard Schwinn 2018 analysis of “Small Business GDP 1998-2014.” These estimates were applied to regional industries’ gross receipts which are estimates of sales, value of shipments, or revenue from the U.S. Economic Census. They are for illustrative purposes only and do not reflect the definitive economic contribution of the Philadelphia Metropolitan Region’s small businesses.

These enormous contributions of small businesses to both economic output and employment are at severe risk due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic lockdown. A 2016 study by the JP Morgan Chase Institute estimated that the median small business has only 27 days of cash reserves on hand, while 25 percent of businesses have only 13 days or less. Meanwhile, the most robust small businesses have between 62 and 100 days of cash reserves [5]. With the most optimistic forecasts for the pandemic’s duration and subsequent lockdown lasting through much of the spring—and with most economists predicting a protracted recession that could last the better part of a year—the median small business is likely to run out of cash before any normalcy returns.

Where’s the Relief?

In recognition of the importance of small businesses and the calamity facing the national and regional economy, the various levels of government have all come up with targeted emergency support programs. The City of Philadelphia quickly organized a $9 million COVID-19 Small Business Relief Fund to provide grants and loans to small businesses, while the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania appropriated $60 million for its COVID-19 Working Capital Access Program to provide working capital financing to small businesses adversely impacted by COVID-19. Both programs were tapped out within a week.

The federal government stepped into the breach on March 27 with the $2.2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act - at the heart of which is the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). Administered by the Small Business Administration through approved lenders, PPP was allocated $349 billion in forgivable loans to help small businesses retain employees for two months, ostensibly long enough to weather the crisis. Within the first 72 hours the program had received far more applications than the $349 billion appropriation could cover, and the U.S. Treasury is poised to ask Congress to appropriate another $200 billion. But considering that small businesses constitute roughly $6 trillion in economic output, it is an open question as to whether even $550 billion in support will be enough to help.

The fact that the U.S. economy was on an historically robust growth trajectory just prior to the onset of crisis gives some economists hope that the recovery may be relatively quick, if the pandemic subsides more quickly than anticipated or if lockdowns can be scaled back. The longer the crisis and the subsequent lockdowns, the more likely it is that there will be mass small business failures; this will undoubtedly have severe long-term effects regionally and nationally.

Works Cited

[1] U.S. Small Business Administration. 2019. “What’s New with Small Business?” Office of Advocacy, U.S. Small Business Administration, Washington D.C. Retrieved from: (https://advocacy.sba.gov/2019/09/24/whats-new-infographic-lets-you-see-the-answers-to-top-small-business-faqs/).

[2] Mills, Karen. 2013. “SBA’s Karen Mills: U.S. competitiveness hinges on the strength of small business suppliers.” The Washington Post, May 6. Retrieved from: (https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/on-small-business/sbas-karen-mills-us-competitiveness-hinges-on-the-strength-of-small-business-suppliers/2013/05/06/03f517b8-b412-11e2-9a98-4be1688d7d84_story.html).

[3] Kobe, Kathryn and Richard Schwinn. 2018. “Small Business GDP 1998-2014.” Office of Advocacy, U.S. Small Business Administration, Washington D.C. Retrieved from: (https://advocacy.sba.gov/2018/12/19/advocacy-releases-small-business-gdp-1998-2014/).

[4] PA Small Business Development Centers. 2018. “Pennsylvania Small Businesses by County.” SBDC Pennsylvania. Retrieved from: (https://www.pasbdc.org/resources/small-biz-stats).

[5] JP Morgan Chase & Co. Institute. 2016. “Cash is King: Flows, Balances, and Buffer Days: Evidence from 600,000 Small Businesses.” Retrieved from: (https://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/institute/document/jpmc-institute-small-business-report.pdf).