Rising Rents in Greater Philadelphia

While housing prices are on the rise during this inflationary period, rents are sharply increasing as well. Since renting is often the first step many individuals and families take into the housing market and remains the only option for many low-income residents, steeply rising rents can have a severe economic impact on a region. In this Leading Indicator, we take a closer look at Greater Philadelphia’s rising rents, the cause, and the impact.

What You Need to Know

- Rents have risen significantly in Greater Philadelphia from 2015 through 2021. By December 2021, the region’s average rent was 9.8 percent higher than it had been in the previous year.

- Average rents across the U.S. are rising at a faster rate than those in Greater Philadelphia. By December 2021, the average annual growth rate for the nation’s average rent was 13.9 percent – 1.4 times greater than Greater Philadelphia.

- Greater Philadelphia’s average rent jumped from $1,604 a month to $1,755 from January to December 2021 – a 9.4 percent increase. Prior to the pandemic, the annual change in rent from January to December in a typical year averaged just 2.5 percent.

- At the national level, average rent increased from January to December 2021 by 13.3 percent. Prior to the pandemic, the average annual increase for the nation’s average rent was about 3.5 percent.

- The stark increases in rent will likely have a serious impact on Greater Philadelphia’s financially vulnerable populations.

- As of 2019, 32.7 percent of households in Greater Philadelphia were renter-occupied.

- As of 2019, more than 51 percent of Greater Philadelphia’s renters were residents of color – a stark overrepresentation since residents of color only make up a third of the region’s total population.

- Just over 27 percent of Greater Philadelphia’s renters are between the ages of 25 and 34 years old.

- Two out of every three households experiencing poverty in Greater Philadelphia are occupied by renters.

- Just under 48 percent of Greater Philadelphia’s renters are rent-burdened or spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent.

- By August 2021, even a person earning the region’s average gross income of $67,400 would be considered rent-burdened.

Recently Rising Rents

Within the past few months, rents have sharply increased both in Greater Philadelphia and across the country. Figure 1 details the annual growth rates of the average rent (calculated by Zillow) in Greater Philadelphia as well as the U.S. from January 2015 to December 2021.

FIGURE 1

SOURCE: Zillow Observed Rent Index (ZORI) from Zillow. A detailed methodology of this calculation can be found here.

Prior to the pandemic, average rents in Greater Philadelphia and the U.S. were relatively stable. From January 2015 to February 2020, Greater Philadelphia’s rent saw an average growth rate of 2.8 percent from year to year. Nationally, rental prices increased by 4.9 percent in January 2015 but by February 2020 rental price growth had slowed to 2.7 percent. Thus, average rents were growing at a relatively consistent rate in Greater Philadelphia while the nation’s average rent was beginning to plateau.

By March 2020, the annual growth rates for rent declined as the typical churn of the housing and rental markets halted during the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Churn in a typical rental market comes from new vacancies. Some of these vacancies come from new construction or conversion of owner-occupied homes or non-residential buildings into rental housing. However, most rental vacancies come from the turnover of existing rental units – when former renters leave to buy a home, move to a new rental unit, get evicted, or die [1]. The pandemic’s initial lockdown disrupted this typical churn. It halted construction projects, prevented “ready-to-buy renters” from purchasing homes, and slowed renter turnover; additionally, government moratoria put a halt to evictions [2,3]. Figure 1 shows that during this time the average rent in Greater Philadelphia and the U.S. increased but at half the rate of previous years.

By the autumn of 2020, shortages in the housing market inflated residential property values and started to impact the rental market [2,4]. The lack of housing inventory prevented many would-be first-time homebuyers from leaving the rental market, and the rental market’s churn continued to stagnate since fewer renters were moving. Many renters had recently been laid off or furloughed in the initial months of the pandemic and moratoria prevented evictions [3,5]. Property owners and landlords who could take advantage of rising property values to recuperate losses began charging higher rents [2,3,5]. In fact, Greater Philadelphia’s average rent jumped from approximately $1,604 a month to $1,755 from January to December 2021 – a 9.4 percent increase. Prior to the pandemic, the annual change in rent from January to December in a typical year in Greater Philadelphia averaged at 2.5 percent. For the U.S., the average rent increased from January to December 2021 by 13.3 percent, far higher than the pre-pandemic annual average of 3.5 percent.

Greater Philadelphia’s Renters

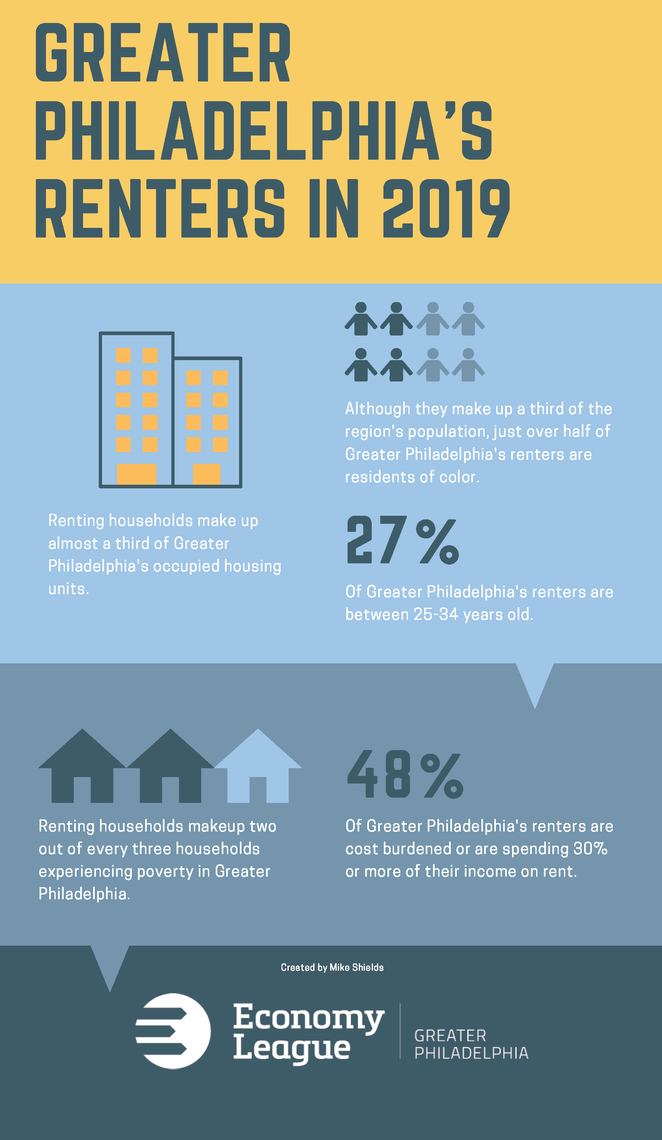

The sharp increases in rent will likely have a serious impact on Greater Philadelphia’s financially vulnerable populations. As figure 2 illustrates, Greater Philadelphia’s renting population is disproportionally comprised of low-income populations, younger age cohorts, and racial and ethnic minorities.

FIGURE 2

SOURCE: Data were obtained from five-year estimates of the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey.

As of 2019, 32.7 of Greater Philadelphia households were renters. They were also 1.8 times more likely to be experiencing poverty than homeowners, 1.9 times as likely to be cost burdened – that is, spending 30 percent or more of their income on rent – than homeowners and 1.8 times more likely to be under the age of 34 years old than homeowners. Additionally, more than half of the region’s renters are residents of color – a significant overrepresentation since people of color comprise only a third of the region’s total population [6].

Thus, sharp rent hikes threaten the financial well-being of already marginalized people—such as communities of color and recent immigrants—as well as younger generations—such as Millennials—inhibiting them from building savings and accessing pathways to homeownership. Additionally, increases in rent will likely push more residents into poverty, considering the already high levels of poverty and cost burden among many of Greater Philadelphia’s renters prior to the pandemic.

Growing Unaffordability

To further illustrate Greater Philadelphia’s increasingly unaffordable rent, figure 3 calculates income levels that would be considered cost- or rent-burden based on the average rent while also graphing the average annual gross income of Greater Philadelphia.

FIGURE 3

SOURCE: Zillow Observed Rent Index (ZORI) from Zillow (a detailed methodology of this calculation can be found here), and average hourly earnings of private employment in the Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD metropolitan statistical area from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Employment Statistics program.

Rents in Greater Philadelphia are becoming increasingly unaffordable for both low- and middle-income earners. For the past few years, average rents have inched closer to Greater Philadelphia’s average income level. The significant jump in average income in 2020 reflects the large pandemic-induced layoffs of lower-wage workers which pushed the region’s average wage (and unemployment levels) higher. By 2021, Greater Philadelphia’s average rent swelled at a much quicker pace than in previous years to the point where, by August 2021, an individual earning the average income in Greater Philadelphia (roughly $67,400) was considered rent-burdened.

What Does the Near Future Hold?

Economists and housing market experts are largely predicting that the housing market will soon see increases in supply but that higher rents are unlikely to ebb [2,3,7]. Once a value threshold is reached, rents typically continue to grow – even in times of economic downturn where they are more likely to plateau than contract. Some economists are even predicting that mortgage rates—which remain at a historic low even with the federal government considering interest rate hikes—will offer far more affordable monthly payments than the cost of rent in the coming months [3].

Though there seems to be little sign of downward pressure on rents, workers may be in a position to command higher wages especially in the wake of the Great Resignation. Pennsylvania continues to be a regional outlier in terms of its stagnant $7.25 an hour wage, and perhaps rising housing costs could make a minimum wage increase more politically salient. The confluence of long-term wage stagnation and rising housing costs will put increasing strain on Greater Philadelphia’s economic competitiveness.

Works Cited

[1] Zuk, Miriam. 2020. “Preventing Gentrification-Induced Displacement in the U.S. - A Review of the Literature and a Call for Evaluation Research.” Pp. 302-316 in The Routledge Handbook of Housing Policy and Planning, edited by Katrin B. Anacker, Mai Thi Nguyen, and David P. Varady. New York City, NY: Routledge.

[2] Sisson, Patrick. 2021. “What’s Driving the Huge U.S. Rent Spike?” Bloomberg CityLab, 5 October. Retrieved from: (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-05/tenants-struggle-with-red-hot-u-s-rental-market).

[3] Squires, Camille. 2021. “Rents in the US are rising even faster than home prices.” Quartz, 22 December. Retrieved from: (https://qz.com/2101421/rents-in-the-us-are-rising-even-faster-than-home-prices/#:~:text=Rental%20prices%20are%20now%20overtaking,demand%20in%20the%20rental%20market.).

[4] Bernstein, Jared, Ernie Tedeschi, and Sarah Robinson. 2021. “Housing Prices and Inflation.” The White, 9 September. Retrieved from: (https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2021/09/09/housing-prices-and-inflation/).

[5] Horowitz, David Mamril. 2021. “With falling rents, lease negotiations abound, but tenants refuse to call San Francisco a renter’s market.” Mission Local, 13 Janaury. Retrieved from: (https://missionlocal.org/2021/01/with-falling-rents-lease-negotiations-abound-but-tenants-refuse-to-call-san-francisco-a-renters-market/).

[6] U.S. Census Bureau. 2020. 2015-2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. Retrieved from: (https://www.census.gov/data.html).

[7] Veiga, Alex. 2021. Risking Rents Taking up Growing Share of Americans’ Income. Associated Press, 4 November. Retrieved from: (https://apnews.com/article/coronavirus-pandemic-business-lifestyle-health-prices-f4f279a4250fa95dd540c6de7247f3d5).