Declining Homeownership in Philadelphia

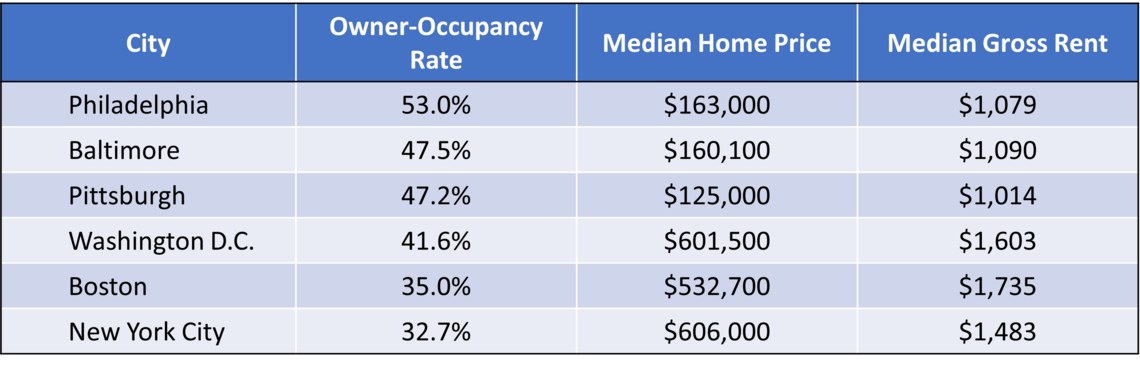

Philadelphia has long been touted as an affordable big city [1]. As shown in figure 1, it has the highest owner-occupancy rate among its peer Northeast cities, at 53.0 percent.

FIGURE 1

SOURCE: Data were obtained from five-year estimates of the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey.

High rates of homeownership are generally considered a boon from an economic development standpoint. Homeownership is a key element of wealth-building in the United States and a significant contribution to a region’s economic well-being. Owning a home enables individuals to accrue equity and take advantage of tax incentives. It stabilizes communities and the municipal tax base, tends to anchor employees to the region, and creates demand for both public and private services including maintenance, restoration, infrastructure, food and supplies, entertainment, and so forth [2]. This is not to say that renting does not also provide economic development incentives or that homeownership comes without economic drawbacks; however much of the current U.S. domestic economic policy aligns toward expanding and incentivizing homeownership, and many municipalities, like Philadelphia, see it as a key strategy in combating poverty and building a stronger tax base.

Yet with the local housing market’s recent boom in sales, driven in part by reduction in supply due to the COVID-19 pandemic, is homeownership becoming less attainable for Philadelphians? This is the question we explore in this Leading Indicator.

Key Takeaways

- At 53 percent in 2019, Philadelphia’s homeownership rate outpaces other Northeast peer cities like New York City, Boston, Washington D.C., Pittsburgh, and Baltimore.

- Since 2006, however, Philadelphia’s homeownership rate has been steadily declining from a high of 58.2 percent.

- Even among most of the city’s major racial and ethnic groups, homeownership is in decline – except for the city’s Asian population, which has seen a ten percent increase in homeownership between 2005 and 2019.

- One possible contributor to declining homeownership in the city is the growing cost of housing – both across the country and in the city.

- While wages in Philadelphia have remained stagnant between 2012 and 2021, Philadelphia’s median residential sale price has increased 0.8 percent per month, equating to a monthly increase of roughly $1,519, when accounting for inflation.

- If Philadelphia’s wages had grown at the same rate as the median sale price of Philadelphia homes during the same period, by July 2021 the average hourly wage in Philadelphia would have been $53.78 or a whopping average annual wage of $111,862.

- As of July 2021, a 77.8 percent gap exists between the growth in median residential sale prices and average wages in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia’s Homeownership Trends

Figure 2 shows how Philadelphia’s owner-occupied housing has been decreasing since 2005. With a steady decline from 2006 to 2012, homeownership seemed to slightly ebb and flow from 2014 to 2018 (estimates made in 2017 contain sampling errors) and taper off by 2019. Yet from 2006—the highest point in the fifteen-year period—to 2019, homeownership in Philadelphia has declined by almost six percent.

FIGURE 2

SOURCE: Data were obtained from single-year estimates of the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2005 through 2019 American Community Survey.

NOTE: 2017 American Community Survey estimates from Philadelphia should be interpreted with caution due to data collection errors.

Homeownership largely seems to be in decline among most of the city’s different racial and ethnic populations. As figure 3 illustrates, homeownership rates only seem to be climbing for the city’ Asian population, with roughly a ten percent increase in owner occupancy between 2005 and 2019. Trend lines for other racial and ethnic populations largely mirror the overall decline in homeownership, except for the city’s Latinx population who seem to have had steeper rates of decline throughout the fifteen-year period.

FIGURE 3

SOURCE: Data were obtained from single-year estimates of the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2005 through 2019 American Community Survey.

NOTE: 2017 American Community Survey estimates from Philadelphia should be interpreted with caution due to data collection errors.

Housing Prices and Local Wages

One possible contributor to declining homeownership in the city is the growing price of housing – both across the country and in the city. While not the only cause, the climbing residential prices of the real estate market are making homeownership less likely for many middle- and low-income groups. Figure 4 illustrates how home prices in the city have significantly outpaced local wage growth.

FIGURE 4

SOURCE: Monthly Redfin Housing Market estimates from 2012 to 2021 and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistic’s Current Employment Statistics.

NOTE: The non-seasonally adjusted U.S. City Average Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers (CPI-U) was used to convert to real dollars.

Since 2015, the median sale price of residential properties in Philadelphia began to climb at an average rate of roughly 0.8 percent per month, when accounting for inflation. This equates to a monthly increase of roughly $1,519 to the city’s median residential sale price. Wages, on the other hand, remained stagnant with an average growth rate of 0.05 percent per month between January 2012 and July 2021, when accounting for inflation; equating to an additional $0.01 increase in average hourly wages per month during the nine-year period.

For further perspective, by July 2021 the average hourly wage in Philadelphia was $30.88 - equating to an average annual wage of roughly $64,000. If wages had grown at the same rate as the median sale price of Philadelphia homes during the same period, by July 2021 the average hourly wage in Philadelphia would have been $53.78 or a whopping average annual wage of $111,862. Instead, a 77.8 percent gap exists between the growth in home prices and average wages in Philadelphia.

Conclusion

Is the decline in homeownership a benefit or detriment to Philadelphia’s economic well-being? While an extensive body of economic development research lists the importance of homeownership in contributing to neighborhood stability, reducing transience and crime, building wealth and equity, stabilizing tax bases, and contributing to local amenities, it is difficult to determine if a changing global economy is no longer awarding homeownership as it had in the past. While these decreases in homeownership may worry some, it should be noted that economically successful cities like New York City, Washington D.C., Boston, and San Francisco are predominantly renter cities. In future Leading Indicators, we will take a closer look at this question to see how the changing nature of residency is altering the economic landscape of Philadelphia.

Works Cited

[1] Houwzer. 2020. “The Cost of Living in Philadelphia: More Affordable Than Most Big Cities.” Houwzer, 28 December. Retrieved from: (https://houwzer.com/blog/the-cost-of-living-in-philadelphia-more-affordable-than-most-big-cities).

[2] Mallach, Alan. 2016. “Homeownership and the Stability of Middle Neighborhoods.” Community Development Innovation Review, 23 August. Retrieved from: (https://www.frbsf.org/community-development/publications/community-development-investment-review/2016/august/homeownership-and-the-stability-of-middle-neighborhoods/).