COVID-19 and Philadelphia’s Food Economy

With statewide closures of non-essential businesses and mandated social distancing resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, many of the region’s food-based businesses have found themselves in dire financial situations. Across the city, restaurants, cafes, bars, and takeout establishments have been forced to close their doors to customers, lay off employees, reduce store hours, adapt to new supply chain demands, and—if possible—establish themselves online. For an industry that normally operates within tight profit margins, Philadelphia’s food economy is being squeezed to the breaking point by the pandemic. In this Leading Indicator, we look at the effects of the pandemic on this critical industry and the local economy.

The Local Food Economy

As the Economy League’s 2019 Good Eats report lays out in detail, Philadelphia’s food-based businesses fuel extensive commercial activity and create thousands of jobs in the region. The food economy accounts for 10 percent of all jobs and 19 percent of all establishments within the city as of 2018. It consists of six primary sectors: production, processing, distribution, retail, hospitality, and waste. Each sector has its own distinct sphere of activity with unique occupation types.

The food hospitality and food retail sectors are the largest segments of the local food economy, and both are in jeopardy as a result of the pandemic. The food hospitality sector includes restaurants, hotels, food service contractors, and caterers. With 54,315 jobs as of 2018, it accounts for 68 percent of the city’s food-related jobs and 7.9 percent of the city’s total employment. The retail sector includes businesses that directly sell food, beverages, and related goods to consumers through brick-and-mortar stores or via online e-commerce platforms. The food retail sector accounts for 21 percent of the city’s food-related jobs and 2.8 percent of the city’s total employment with 19,294 jobs as of 2018. Many food-related retail businesses, like supermarkets and convenience stores, have been labeled as “essential” businesses during this crisis and have ramped up employment. However, others—like beer distributors, bakeries, and other specialized food markets—have had to close their doors to customers.

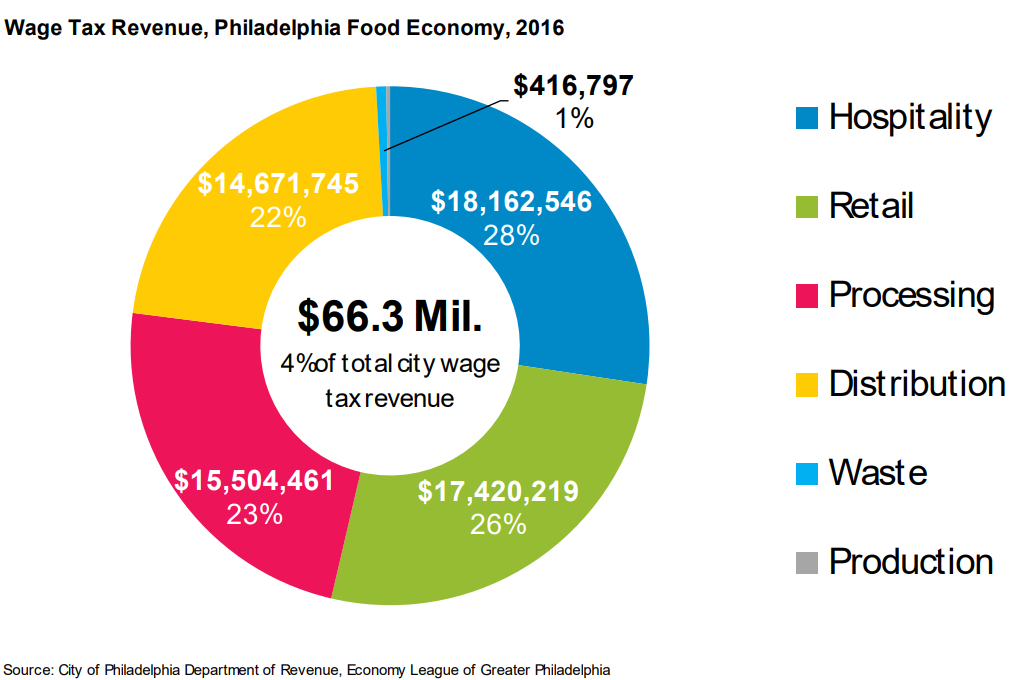

Both sectors also contribute significantly to the city’s local tax revenue. Figure 1 shows the contributions to the city’s 2016 wage tax payments by food economy sector. Both the food hospitality and food retail sectors (at 28 percent and 26 percent respectively) outpace all other food-related sectors with their wage tax contributions.

NOTE: Figure 1 can be found on page 7 of the Economy League's Good Eats report

While offering a variety of employment options, most of the occupations within the food hospitality and retail sectors are low-wage positions with relatively low barriers to entry and few career pathways. In fact, the average annual wage in 2018 for both sectors were far below the city’s average annual wage of $65,824 ($25,794 for the hospitality sector and $29,983 for the retail sector). Most of the low-wage jobs within these sectors are at risk of layoffs or a loss of hours as business owners seek to reduce expenses in the wake of the pandemic – especially since labor costs typically constitute 25-35 percent of expenses in food hospitality and retail [1]. The cumulative impact of the loss of these jobs will undoubtedly have ripple effects throughout the local economy.

Loss of Employment in the Food Economy

A Pennsylvania Restaurant and Lodging Association official recently predicted that roughly a third of the city’s restaurants may not reopen as a result of the pandemic. When considering how integral the food hospitality and retail sectors are to the local economy—especially with Philadelphia’s recent emergence as a “foodie” destination—if this stark prediction is true then the fallout will be enormous.

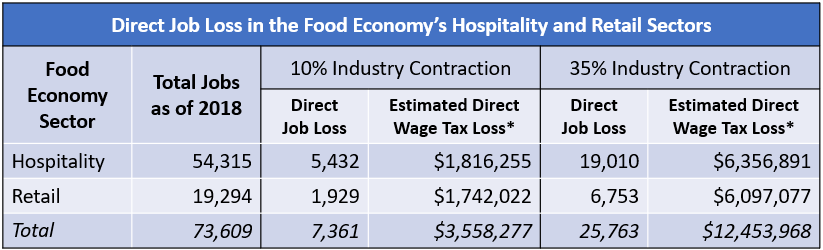

Job losses mean lost wages, and wages fuel the local economy. They allow workers to stimulate other industries via consumption of goods and services, as well as act as an important source of revenue for the City of Philadelphia. In fact, roughly 40 percent of the city’s tax revenues derive from the Philadelphia Wage Tax (Philadelphia is unusual among major U.S. cities in that it derives most of its revenue from taxes on personal and business income rather than on property or sales taxes). To illustrate the impact of job losses in these sectors, in Figure 2 we estimated the direct job loss and subsequent wage tax loss that would result from a 10 percent and 35 percent industry contraction – as best- and worst-case scenarios.

NOTE:

* Estimated Direct Wage Tax Loss is calculated as a 10 or 35 percent reduction of wage tax revenue generated from each sector in 2016 (see Figure 1 above)

Figure 2 shows that a 10 percent labor force contraction in the food hospitality and retail sectors would mean a loss of 7,360 jobs and roughly $3.6 million in lost wage tax revenue for the city; a contraction of 35 percent—roughly equivalent to the Pennsylvania Restaurant and Lodging Association official’s prediction—would equate to a loss of more than 25,760 jobs and roughly $12.5 million in lost wage taxes.

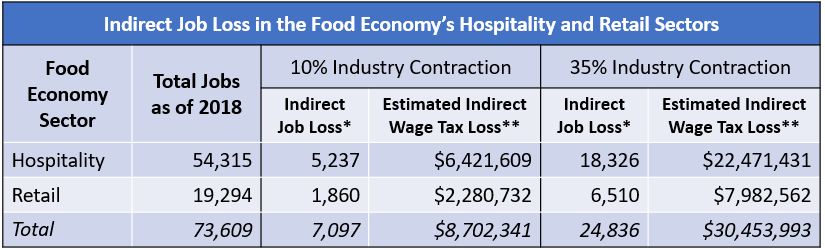

While these numbers are striking, they represent only a portion of the total impact. The direct loss of thousands of jobs in the food economy would cascade into losses in other industries that are powered by the income from food economy workers, as well as translate to further losses in city tax revenue. The reduction of hours, furloughs, and layoffs reduce the flow of consumption and stifle economic activity across both business-to-consumer and business-to-business sectors. For example, a massive layoff in a corporate office negatively effects the various suppliers of office materials, technology, security, as well as the lunch establishments and other service businesses that depend upon office workers. Layoffs ripple across sectors. To demonstrate these potential cascading impacts of labor force contraction in the food economy, Figure 3 uses employment multipliers and estimated median earnings for Philadelphia residents in 2018 to show indirect job and tax revenue losses.

FIGURE 3

NOTE:

* Indirect Job loss in both sectors are calculated using a 0.964 multiplier for “Food Services and Drinking Places” on the direct jobs lost for each sector from Figure 2 [2]

** The Estimated Indirect Wage Tax Loss is an illustrative example of wage tax loss and is inherently an overestimation. It is the summation of wage tax payments if each indirect job loss represented one individual living in Philadelphia with a wage matching the median earnings for the City of Philadelphia in 2018 - approximately $31,675, according to 5-year estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

Figure 3 reveals that a 10 percent labor force contraction in the food hospitality and retail sectors would lead to as many as 7,097 lost jobs in other industries and roughly $8.7 million in lost wage tax revenue for the city, while a 35 percent contraction would lead to as many as 24,836 lost jobs, which would in turn lead to about $30.5 million in lost wage tax revenue. Indirect jobs comprise induced jobs, such as those in sectors that supply the food hospitality and retail sectors (e.g., food production, processing, and distribution, as outlined in detail in the Good Eats report), as well as jobs in sectors that are currently supported by demand driven by food hospitality and retail workers’ wages.

So, accounting for both direct and indirect impacts, a 10 percent labor force contraction in the food hospitality and retail sectors could lead to roughly 14,500 lost jobs and $12.3 million in lost wage tax revenue, while a 35 percent contraction could lead to roughly 50,600 lost jobs and $43 million in lost wage tax revenue.

The Canary in the Coal Mine

As the pandemic escalates toward its eventual apex, many food-related enterprises face the stark possibility of being driven out of business. The $2.2 trillion stimulus package signed into law on March 27 holds out some hope of relief for business owners, at least those who can hang on long enough to apply for forgivable Small Business Administration loans and commit to retaining employees during the duration of the crisis. For those workers who are laid off, enhanced unemployment benefits will cushion both the personal blow and the impact to the broader consumer economy.

In any case, food-related businesses are a vital part of both the local economy and the urban ecosystem; the worst-case scenario will deal a stinging blow to the hard-won vibrancy of many neighborhoods in this city.

Works Cited

[1] Hall, Mitchell. 2018. “How to Efficiently Manage Labor Costs for Your Restaurant.” Upserve, September 5. Retrieved from: (https://upserve.com/restaurant-insider/labor-cost-guidelines-restaurant/).

[2] Bivens, Josh. 2019. “Updated employment multipliers for the U.S. economy.” Economic Policy Institute, January 23. Retrieved from: (https://www.epi.org/publication/updated-employment-multipliers-for-the-u-s-economy/).