Expanding Transportation Access

As the literal link between people and jobs, transportation plays a critical role in enabling access to opportunity. In Greater Philadelphia, a rich legacy of prior investments has endowed us with extensive transportation infrastructure assets. However, many of the region’s roads, transit routes, and rail lines – designed and built during a different era – are ill-equipped for today’s commuting volumes and patterns.

Over the last several decades, the distance between many of the region’s workers and jobs in growing industries has increased, and the average commuting time for a typical resident has risen significantly. As a result, access to transportation options that connect to the region’s employment centers has become markedly uneven across Greater Philadelphia.

Families living in areas with shorter average commute times have a better chance of moving up the economic ladder than those living in areas with longer average commute times.

Today, people who live in communities that lack effective and convenient transportation connections face an impediment to economic advancement and sustained prosperity. Recent research has found commute time to be a key predictor of upward social mobility in the United States. Families living in areas with shorter average commute times have a better chance of moving up the economic ladder than those living in areas with longer average commute times.

Businesses also benefit from broad access to transportation. Firms in areas with better transit coverage have lower employee turnover rates than firms in areas with less extensive coverage or none at all. Intuitively, this makes sense – the harder it is for a person to get to his or her job, the less likely he or she is to stick with it for the long term. The benefits of broad transportation access are wide, and they accrue to both individuals, for whom mobility is a critical component of economic prosperity and quality of life, and to the region at large.

Greater Philadelphia stacks up fairly well against other metros on top-level commuting metrics…

On measure of connectivity and access, our region performs fairly well compared to other large US metros. Greater Philadelphia’s average commute time of 28.5 minutes and typical commute distance of 7.8 miles are among the shortest of the ten largest metros in the US.

AVERAGE TRAVEL TIME TO WORK, BY METRO AREA (2013)

DISTANCE (MILES) OF TYPICAL COMMUTE BY METRO AREA

Approximately eight in ten people in the region commute to work by car. While this share is below the national average of 86 percent, it is higher than other Northeast metros like Boston (76 percent), Washington, DC (76 percent), and New York (58 percent). Just under 10 percent of workers in our region take public transportation to work – well above the national average of 5 percent but lower than peer East Coast metros.

MEANS OF TRANSPORTATION TO WORK, BY METRO AREA (2013)

...but within the region, quality of transportation access is influenced by location, income, race, and other factors.

While Greater Philadelphia fares well on top-level indicators of transportation access, an examination of commutes in more than 300 ZIP codes within Greater Philadelphia reveals significant variation in average travel time to work across communities in the region. Several ZIP codes in Wilmington boast the shortest average commutes at 18-20 minutes, while communities on the periphery of the region, like Kintnersville in upper Bucks County, fall on the opposite end of the spectrum, with average commutes of 35-39 minutes.

AVERAGE TRAVEL TIME TO WORK IN GREATER PHILADELPHIA, BY ZIP CODE (2013)

Commutes for workers in poor urban neighborhoods are among the longest in the region.

Counterintuitively, several ZIP codes in urban, ostensibly transit-rich neighborhoods in Philadelphia are among those with the longest commutes in the region. The average commute in North Philadelphia’s 19132 ZIP code, which includes parts of the Strawberry Mansion neighborhood, is nearly 38 minutes – 33 percent longer than the regional average. And in West Philadelphia’s 19139 ZIP code, which straddles SEPTA’s Market-Frankford line, the average commute time is nearly 37 minutes.

African Americans in the region spend 20 percent more time getting to work than white workers do.

Many of the Philadelphia neighborhoods that have the longest commutes are predominantly African American. In 19132, 94 percent of residents are African American; in 19139 the share is 92 percent. Regionally, this adds up to a marked disparity in average commute times by race: on average, African Americans in the region spend 20 percent more time getting to work than white workers do. In fact, black workers in all of the ten largest US metros have longer average commutes than white workers, though Greater Philadelphia’s spread of 20 percent is among the largest in the group.

AVERAGE TRAVEL TIME TO WORK IN GREATER PHILADELPHIA, BY RACE (2012)

Parsing the underlying elements that contribute to commute time disparities is complex, though it’s safe to say that the mode of transportation a worker uses to commute affects how long it takes him or her to get to work. And, on average, there is a striking difference in how workers of different races and income levels get to work in Greater Philadelphia.

Low-income workers rely heavily on public transportation to get to work…

African Americans rely much more heavily on public transportation for their trips to work than do workers of other races, using transit for 24 percent of commutes. Only 6 percent of white workers, in contrast, commute via public transportation. In neighborhoods in North and West Philadelphia, transit ridership rates are even higher: in 19132, 41 percent rely on transit to get to work; in 19139, the share is 48 percent. Taken out of context, this level of transit usage could be viewed as an example of good urbanism. Some might even point to the high ridership levels in these neighborhoods as models for other communities where vehicular congestion compromises productivity and quality of life. However, while the proximity and frequency of transit in these neighborhoods no doubt contribute to high ridership levels, low incomes are likely the primary driver. At around $24,000 per year, the median household income in both 19132 and 19139 is less than 40 percent of the regional median income of nearly $61,000. These income levels put car ownership out of reach for many individuals and families in these neighborhoods – Census data show that half of households in both ZIP codes do not have access to a vehicle – meaning they have little choice but to use transit or walk to get to work. It should come as no surprise that there is a link between how much a person makes and the mode of transportation he or she relies on to get to work. In Greater Philadelphia as in the United States as whole, the lower a person’s income, the more likely he or she is to commute on foot or by transit.

MEANS OF TRANSPORTATION TO WORK BY EARNINGS IN GREATER PHILADELPHIA (2013)

…and the average transit commute takes longer than the average commute by car.

And the fact of the matter is that on average, workers in Greater Philadelphia who take public transit to work have significantly longer commute times than those who get to work by automobile. 32 percent of commutes via public transit in our region are 60 minutes or longer. By comparison, only 8 percent of commutes by automobile are 60 minutes or longer.

workers in Greater Philadelphia who take public transit to work have significantly longer commute times than those who get to work by automobile

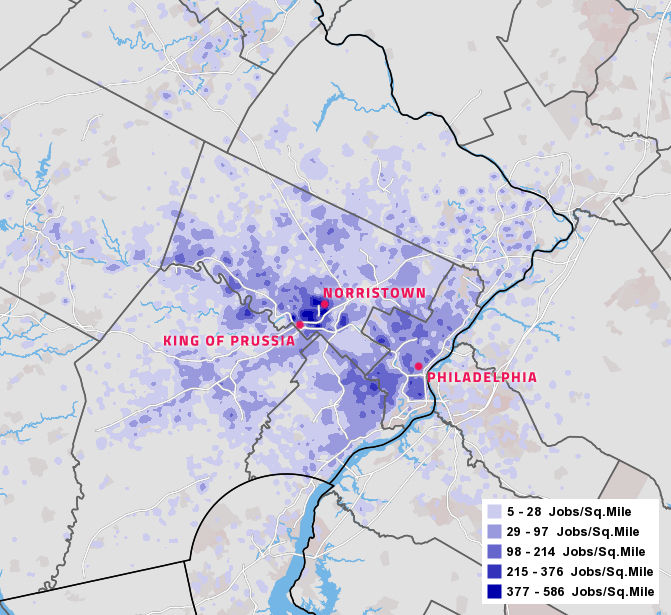

For a region with an extensive, multi-modal transit system that accommodates more than 300 million passenger trips per year, this is remarkable. But the extended duration of the average transit commute in Greater Philadelphia is due in no small part to the decades-long trend of “job sprawl” in the region. The gradual shift of many jobs away from transit-accessible locations has compromised the effectiveness of our transportation system, decreasing job access in many core communities where car ownership is out of reach.

COMMUTE LENGTH BY MEANS OF TRANSPORTATION IN GREATER PHILADELPHIA (2013)

The decentralization of jobs has made our transit network less effective and has compromised transportation access in the region.

A 2009 Brookings study found that nearly 64 percent of jobs in Greater Philadelphia are located more than 10 miles from downtown, making our region one of the most decentralized large metros in the US from an employment perspective. And the spatial mismatch between people and jobs has been getting worse: between 2000 and 2012, the number of jobs near the average Greater Philadelphia resident fell by 10 percent.

Over the years, the decline in the number of jobs in the city of Philadelphia and other core communities coupled with the rise of isolated suburban employment centers that are poorly served by transit has reduced transportation access across the region and limited economic opportunity for people of limited means.

King of Prussia: A case study

Today, King of Prussia is the largest job center in the region outside of the city of Philadelphia, offering employment opportunities across skill and income levels. But workers without access to a vehicle have a hard time getting to and from the area.

And yet in 2012, 71 percent of people working in KOP lived at least 10 miles away, and 24 percent lived at least 25 miles away. These figures have grown over the past 10 years: in 2002, 67 percent of workers lived at least 10 miles away, and 19 percent lived at least 25 miles away.

WHERE KING OF PRUSSIA WORKERS LIVE

*Map represents the relative spatial concentration of where people who work in zip code 19406 live .

SOURCE: US Census Bureau, Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics (2012)

Today more than 8,000 people who work in King of Prussia live in Philadelphia. Transit service between the city and King of Prussia is limited and unreliable, operating on-time just 65 percent of the time. With limited transit options, the only reliable transportation option is to drive. And this makes the prospect of working in King of Prussia difficult for many people of limited means in the city, in turn narrowing opportunities for them to advance economically.

How can we pave the way to expanded transportation access in Greater Philadelphia?

Substantially improving transportation access in the region is a long-term proposition. It will require finding ways to reverse job sprawl and making strategic investments in our transit network. Achieving these goals will require navigating complex political and fiscal realities over years and decades, so a shared vision is critical to maintaining focus and providing long-term direction for planners and policymakers.

SET AND STICK BY POLICIES THAT CLUSTER HOUSING AND EMPLOYMENT.

Perhaps most important to this effort is a shared, long-range land use plan for the region that prioritizes clustering of housing and jobs in mixed-use centers well served by roads, transit, and alternative transportation options. As the developer and steward of the federally-mandated long-range transportation plan for the region, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) has charted a plan for focusing future development and transportation investments in established population and employment centers. The smart growth approach to development embraced by DVRPC is often touted for the economic and environmental benefits it can yield for communities, but it can also yield a significant opportunity dividend by strengthening connections between people and jobs and expanding access to transportation. By emphasizing investment in centers, promoting affordable and accessible housing, and increasing accessibility and mobility, DVRPC’s Connections 2040 plan lays out a framework for effectively managing growth and enhancing transportation access across the region.

In developing the long-range plan, DVRPC also uses an Environmental Justice assessment to identify populations that may be adversely or disparately impacted by transportation and regional planning decisions. By using this tool, DVRPC can determine what transportation service gaps exist for disadvantaged or underserved groups, which helps inform regional transportation investments.

While regional planning is critical, decisions made at the municipal level ultimately inform the course of our region’s development. Through progressive zoning, strategic tax incentives, and other targeted regulatory mechanisms, local jurisdictions can enhance transportation access by shaping how and where people reside and jobs located in their communities.

In an effort to create a more vibrant and accessible community in King of Prussia, Upper Merion Township and the King of Prussia Business Improvement District worked together to rezone the area encompassing the King of Prussia business park to allow for denser, mixed-use development and promote alternative transportation options and pedestrian-friendly design standards. Adopted in September 2014, the new mixed-use zoning district sets the stage for a different – and more accessible – approach to development in King of Prussia.

PURSUE STRATEGIC INVESTMENTS TO EXTEND TRANSIT TO UNDERSERVED REGIONAL EMPLOYMENT CENTERS.

In addition to prioritizing land use policy that brings together people and jobs, strategic investments to extend the region’s transit system to existing employment centers without reliable service will help expand access. That’s why the World Class Infrastructure agenda prioritizes strengthening connections between the region’s economic hubs as a strategy to both drive growth and expand opportunity. SEPTA’s proposed extension of the Norristown High Speed Line would create a critical transit link between King of Prussia and Philadelphia as well as Norristown and other destinations in Montgomery and Delaware Counties. This extension could help reduce heavy congestion on I-76 while providing better access to King of Prussia for both workers and shoppers.

PRIORITIZE INITIATIVES THAT EXPAND ACCESS IN THE SHORT TERM.

In the shorter term, advancing transportation demand management (TDM) programs can help maximize the efficiency of the existing transportation network and extend the reach of existing transit assets. DVRPC is responsible for facilitating the development of the federally-mandated Coordinated Human Service Transportation Plan (CHSTP) for the region, and is in the process of updating and expanding the current plan to align with the White House’s Ladders of Opportunity agenda. The current CHSTP, developed in 2007, places an emphasis on improving job access, calling for program funds to be used to expand off-peak service on key transit routes, developing partnerships to serve areas not served by traditional transit, and investing in last-mile connectors.

So-called last-mile connectors can be an effective way to extend the reach of fixed-route transit lines and expand transportation access while reducing vehicular congestion. In King of Prussia, theconnector is a commuter shuttle bus service managed by the Greater Valley Forge Transportation Management Association (GVF) in partnership with the King of Prussia Business Improvement District that connects King of Prussia business park employees to SEPTA Regional Rail at the Norristown Transportation Center and Wayne Station on weekdays during the morning and evening rush hours. Transportation management associations across the region, including TMACC in Chester County, TMA Bucks in Bucks County, and Cross County Connection in South Jersey manage commuter shuttles that connect workers who rely on public transportation for their commute to jobs located away from transit access.

Strategic enhancement of bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure can also expand access to jobs for people in underserved communities. While the overall share of commuters who walk or bike to work is small compared to other modes, the share has been growing, particularly in areas where safe and convenient trails and facilities are integrated into the broader transportation network.

Greater Philadelphia has seen significant investment in bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure in recent years, with new trail development led by the Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Utilities in Philadelphia, planning departments in nearly all of the region’s suburban communities, and the Circuit Coalition, a collaboration of non-profit organizations, foundations, and agencies working to advance completion of a connected regional network of trails called The Circuit.

In designing the bike share program Indego, which launched this spring, the City of Philadelphia made a commitment to provide underserved neighborhoods access to the system. A third of the 600 bikes in the Indego system are located in low-income neighborhoods, and users have the option of paying with cash if they don’t have a credit card. The Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia actively works to promote Indego in neighborhoods near the new stations. Philadelphia’s program is the first in the country to launch with cash payment as an option to any resident, regardless of income.

The road ahead

Looking forward, there are reasons to be optimistic about transportation access in Greater Philadelphia. With the 2013 passage of dedicated, comprehensive state transportation funding in Pennsylvania, SEPTA is now in position to plan for enhanced operations and targeted system expansion to address many of these challenges. Many local government agencies and a growing number of civic partners are paying more attention to the value of expanding transportation access in the region. Ultimately, however, progress will depend on the extent of resources available to invest in the kinds of long-term improvements that will make a lasting difference. Here the buck stops at the federal government. Timely and decisive action from a stalemated Congress on long-term transportation funding legislation is critical to advancing efforts to expand transportation access and unlock opportunity here in Greater Philadelphia and across the country.

READ MORE ABOUT EXPANDING OPPORTUNITY

READ MORE ABOUT SUPPORTING UNDERSERVED ENTREPRENEURS

READ MORE ABOUT MOVING WORKERS FROM LOW-WAGE JOBS TO FAMILY SUSTAINING CAREERS