Greater Philadelphia’s Healthcare Industry and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Greater Philadelphia’s large and robust healthcare industry has long been a vital economic asset. The centrality of this sector has only been amplified during the public health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. While many healthcare workers have been deemed essential personnel during this time, others have faced furloughs and layoffs in the wake of the pandemic’s economic lockdown. Local health systems have struggled during these past weeks in the wake of executive orders severely curtailing and even eliminating non-urgent care and elective procedures, leading to greatly reduced revenue streams. In this Leading Indicator, we focus on Greater Philadelphia’s healthcare industry and its workforce and explore potential changes that could have major implications for workers in the post-pandemic period.

Key Takeaways

- At 12.7 percent in 2019, the concentration of healthcare occupations in Greater Philadelphia outpaces other major U.S. metropolitan regions.

- The healthcare workforce saw a substantial rise in home and personal care professions prior to the pandemic that may only increase following the end of the crisis.

- African American/Black representation in Greater Philadelphia’s healthcare workforce far outpaces national estimates while the region’s Latinx/Hispanic representation lags national estimates.

- While work has intensified for many healthcare workers, some face furloughs and layoffs as non-urgent care and elective procedures shrink revenue streams for healthcare systems.

- The region’s healthcare industry will likely see greater integration of tech and innovation along with the adoption of more public-health-oriented frameworks following the end of the COVID-19 pandemic; this could have major implications for the workforce.

Greater Philadelphia’s Healthcare Workforce Prior to COVID-19

Healthcare in the U.S. originated in Philadelphia with the founding of the nation’s first hospital at what would become the University of Pennsylvania [1]. From these humble beginnings, Greater Philadelphia’s healthcare industry grew and diversified to become the leading employer among the region’s industry sectors [2]. Occupations in this industry are often separated into “Healthcare Practitioners and Technical Occupations”—or those who directly dispense medical or clinical treatment or conduct research—and “Healthcare Support Occupations”—those that assist with medical treatment and physical care. Example professions among practitioners include doctors, physicians, nurses, surgeons, researchers, and pharmacists, while healthcare support occupations include home and personal health aides, nursing assistants, orderlies, medical equipment preparers, and all manner of specialized treatment aides. With this diversity of professions and the large concentration of health systems in the region, the healthcare industry and its workforce have long been a bulwark of the Greater Philadelphia economy.

As of 2019, Greater Philadelphia’s healthcare workforce accounted for roughly 365,670 jobs or 12.7 percent of the total regional workforce – one of the highest concentrations among major U.S. metropolitan regions [3]. Figure 1 illustrates the size of the region’s healthcare workforce by comparing it with other major U.S. metropolitan regions in 2019. Greater Philadelphia’s 12.7 percent concentration outpaces other major metropolitan regions like New York City (11.9%), Los Angeles (11.0%), Chicago (9.3%), and Dallas (8.5%). While it is difficult to calculate the economic impact of such a large and multifaceted regional industry, the Hospital and Healthsystem Association of Pennsylvania estimated that Greater Philadelphia’s hospital systems alone account for roughly $17.9 billion in direct economic impact – measured as the amount hospitals spend on goods and services needed to provide health care services and support hospital and health system operations, and the amount they pay for employee salaries, wages, and benefits [4].

FIGURE 1

NOTE: Data for this graph were obtained from annual estimates from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) survey. The Healthcare Workforce is operationalized as all occupations under the Healthcare Practitioners and Technical Occupations and Healthcare Support Occupations categories.

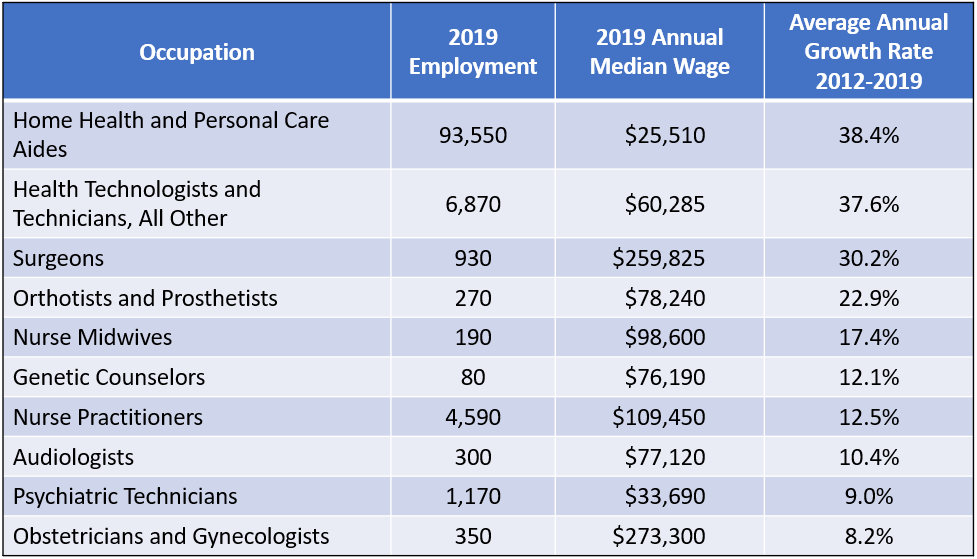

Greater Philadelphia’s healthcare workforce has also been continually growing. Estimates from the Current Employment Statistics survey report that the region added an average of 9,000 jobs per year since 1990 [2]. Much of this recent growth stems from a few fast-growing occupations. Figure 2 shows the top ten fastest growing positions within Greater Philadelphia’s healthcare workforce from 2012 to 2019 along with their median annual wages. Some of these fast-growing healthcare occupations demonstrate the industry’s integration of new technologies and innovative treatments – for example, Genetic Counselors. Interestingly, however, the fastest growing profession—Home Health and Personal Care Aides—is six times the size of the other occupations but has the smallest annual wage at $25,510. It also is the only occupation to come from the Healthcare Support subsector while all the others are from the Healthcare Practitioners and Technical Occupations subsector. This rise in healthcare support reflects the increased demand for more medical and physical assistance for the nation’s aging population. Some of the other Healthcare Practitioners and Technical occupations reflect this trend as well – specifically the Orthotists and Prosthetists, Audiologists, and Psychiatric Technicians. There may be a greater need for these support occupations as large generational cohorts, like the Baby Boomer generation, reach old age.

FIGURE 2

NOTE: Data for this graph were obtained from annual estimates from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) survey. Many healthcare occupations listed here are grouped together based on measurement and occupational title changes during the given time-period.

The region’s healthcare workforce is also relatively racially and ethnically diverse compared to the nation as a whole. Figure 3 shows the racial and ethnic composition of Greater Philadelphia’s Healthcare Practitioners and Technical Occupations from 2012 to 2018 while Figure 4 shows similar representation among Healthcare Support Occupations. Both compare racial and ethnic representation in Greater Philadelphia’s healthcare workforce with that of the U.S. In Greater Philadelphia, African American representation in both Healthcare Practitioners and Technical Occupations and Healthcare Support Occupations far outpaces national representation at 17.1 percent and 48.7 percent in 2018, respectively. In fact, African Americans have constituted the majority in Healthcare Support Occupations in Greater Philadelphia since 2012 – surpassing national representation in 2018 by 24.3 percent. Latinx/Hispanic representation in both healthcare categories, on the other hand, remains far below national estimates – with Greater Philadelphia trailing the nation by 4.8 percent in Healthcare Practitioners and Technical Occupations and 8.8 percent in Healthcare Support Occupations. Since this is among the fastest-growing demographics in the region, it will be important to identify and address barriers to entry for Latinx/Hispanic workers.

FIGURE 3

FIGURE 4

NOTE: Data for both Figure 3 and Figure 4 were obtained from one-year estimates of the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

The Non-Pandemic-Proof Healthcare Workforce

While a large number of occupations in the healthcare industry have been deemed essential for navigating through the pandemic, many of the region’s healthcare workers have been furloughed and even laid off since funding, resources, and attention have been redirected to manage the crisis. Declines in non-urgent care visits and elective procedures—a major source of revenue for many private medical practices as well as health systems—forced many of the region’s healthcare institutions to furlough their non-clinical staff [5]. Many general practitioners, specialists, non-resident physicians, surgeons, and support staffs were given the option of taking voluntary furloughs or facing layoffs. Workers in Healthcare Support Occupations are particularly vulnerable since many of their duties center around non-urgent care. Since these occupations account for 47 percent of the region’s total healthcare workforce [3], the impact of attrition could be quite detrimental to the local economy. In fact, initial unemployment claims from the Education and Health Services industry sector accounted for 17.2 percent of the total initials claims filed in Southeastern Pennsylvania in April 2020 – the second highest rate among all industry sectors within the region (only the Trade, Transportation, and Utilities sector was higher at 20.3 percent) [6].

Many hospital systems are also projecting major losses for the second quarter of the calendar year. The University of Pennsylvania Health System recently projected a $450 million loss from March to June 2020 while Einstein Healthcare internally projected a $70 million loss [3]. Hospitals that are not part of major research institutions or academic medical systems are at risk of greater losses since funds are tighter and opportunities for cost-shifting are scarce. As illustrated locally by the controversial closure of Hahnemann University Hospital in 2019, healthcare institutions that primarily serve marginalized populations were already in precarious financial health even in the strong pre-COVID economy; the impact of the pandemic will likely push many of them over the edge.

Future of Greater Philadelphia’s Healthcare Workforce

Perhaps analogous to the tech sector (as we discussed in a previous Leading Indicator), the COVID-19 pandemic may present an opportunity for Greater Philadelphia’s healthcare industry to pivot in a new direction. The crisis has revealed the cracks in the healthcare system – access tied to employment, the critical significance of social determinants of health, supply chain risk – that ought to align post-pandemic recovery efforts around equity and inclusion. A “rebooted” regional healthcare systems will need to address these and other issues brought into sharper focus during the crisis to keep Greater Philadelphia at the forefront of health innovation and care.

Already on a trajectory to develop so-called “future of work” plans, it is likely that leading institutions will pick up the pace on adoption of new technologies to better predict, prepare for, and confront future health crises in the immediate wake of the pandemic. Telemedicine or telehealth along with other new technologies that provide treatment and care in nontraditional settings will likely receive greater attention and investment following the end of the pandemic, since sustained resiliency will require an updated infrastructure to address future health crises. The region’s healthcare workforce will likely see growth in more tech-oriented healthcare occupations in fields such as bioengineering, biotech, and healthcare analytics. In addition, traditional public health surveillance techniques like contact screening will be updated with new “big data” and real-time methodologies for better prediction and analysis. While the healthcare industry was already seeing a rapid infusion of technology solutions, it is highly likely that the pandemic will accelerate innovation and reward early and successful adopters.

In addition to the infusion of tech, the pandemic may also increase opportunities for personalized care and treatment. This brief has shown how healthcare support occupations are growing to accommodate an aging population. With such a large proportion of pandemic-related deaths occurring in traditional care facilities like nursing homes, assisted living, and rehabilitation centers, the movement away from such settings could accelerate (link). The healthcare workforce may continue to see growth in personal and home care aide occupations, and general practitioners may spend more time virtually or physically visiting patients rather than holding office hours.

The end of the pandemic may also steer more funding toward public-health-oriented programming that addresses the social determinants of health. Shaped in part by regulations borne out of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), many private payers were already considering the economic value of treating the root causes of chronic diseases and conditions such as poverty, limited access to healthy food, quality housing and healthcare, as well as the impact of structural racism, sexism, and homophobia prior to the COVID-19 pandemic [7]. This crisis has repositioned the importance of public health frameworks in treating disease and may call for more cross-sector collaboration among private-payers, hospital systems, and community health organizations in addressing health disparities. This will undoubtedly present new opportunities for program and project management positions within the region’s healthcare industry along with more opportunities to support an often under-funded public health system.

Finally, this crisis may force a major rethinking of the business model driving the U.S. healthcare system. Organized around employer-provided health benefits, the system is ill-equipped to work sustainably during periods of mass unemployment. With a presidential election looming, an emerging consensus that the public health system did not perform optimally at the outset of the crisis, and with partisan battle lines starkly drawn, the state and future of the healthcare system will almost certainly be a key site of debate and contention. While outcomes of that debate are impossible to predict, any changes that divert revenue streams from non-urgent care visits and elective procedures—important to the solvency of so many health systems—will lead to major pivots on the part of these systems.

Greater Philadelphia’s large healthcare industry, and the large workforce that powers it, has been at the forefront of innovation and care for over 250 years. The next twelve to eighteen months are likely to see some significant changes that could have major implications for both the institutions and the workers within this industry.

Works Cited

[1] McGovern, Bob. 2011. “Timeline: A History of Area Medical Innovations.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 9. Retrieved from: (https://www.inquirer.com/philly/health/special_reports/Timeline_A_history_of_medical_innovations.html).

[2] Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. 2020. “Series SMU42379806562000001, All Employees, In Thousands for the Health Care and Social Assistance Industry in the Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD Metropolitan Statistical Area from 1990 to 2020 (Seasonally Adjusted).” Current Employment Statistics. Retrieved from: (https://www.bls.gov/data/).

[3] Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. 2019. Total Employment for Healthcare Practitioners and Technical Occupations and Healthcare Support Occupations for the Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD Metropolitan Statistical Area from 2012 to 2019.” Occupational Employment Statistics. Retrieved from: (https://www.bls.gov/data/).

[4] Siegel, Sari & Ayse Yilmaz. 2019. “White Paper: Beyond Patient Care: Economic Impact of Pennsylvania Hospitals 2018.” The Hospital and Healthsystem Association of Pennsylvania (HAP). Retrieved from: (https://www.haponline.org/Resource-Center?resourceid=288).

[5] Brubaker, Harold. 2020. “Tower Health to furlough at least 1,000 workers as COVID-19 wreaks havoc at hospitals.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 21. Retrieved from: (https://www.inquirer.com/business/health/tower-health-covid-19-furloughs-1000-20200421.html).

[6] Center for Workforce Information & Analysis, PA Department of Labor & Industry. 2020. “Pennsylvania Regular UC Benefits - April 2020.” Retrieved from: (https://www.workstats.dli.pa.gov/Products/Pages/Products%20By%20Geography.aspx).

[7] Wagner, Robert F. 2018. “Promoting Prevention Under the Affordable Care Act.” Annual Review of Public Health, 39: 507-524. Retrieved from: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013534.